I remember learning, or rather being told, many years ago, before I knew much about wine (or much about anything, for that matter), that buttery Chardonnay was déclassé. I learned further this was caused by a process called malolactic fermentation, and while I didn’t find the butter particularly objectionable, I was at the time both naïve and aspirational, so decided to avoid all wines treated to that process.

Whatever it was.

I remember learning, years later, that all Chablis, which is a Chardonnay I love, goes through malolactic. That most champagne does, too, and white Burgundy (also Chardonnay). Almost all red wines. Most orange wines, and natural wines, and even some rosé, especially natural rosé. And no, the results don’t always taste buttery. (Anyway, what’s wrong with buttery?)

And so to save you, dear reader, from the muddled state I endured at the start of my wine education, I present my best attempt to cover this magnificent microbial process.

One lump, or two?

Wine is a fermented product, its intoxicating charms the result of yeast chomping on grape sugar, converting it to ethanol, and burping out carbon dioxide gas. This is the so-called primary fermentation, and you can’t make wine without it.

But many wines, arguably the majority of wines, go through a second process, which is called a “fermentation” even though, strictly speaking, it’s a conversion of one acid to another. This process is carried out by bacteria, specifically lactic acid bacteria, and is called malolactic fermentation (MLF or malo).

Hold on. What are lactic acid bacteria?

Lactic acid bacteria, or LAB, are important to the world’s cuisines. Fermentations using LAB have been used for centuries to culture and preserve a vast range of foods, including milk, meat, fish, vegetables, legumes, and cereals. It gives us tangy yogurt, snappy kimchi, succulent salumi, savory fish sauce, sour Lambic, and so much more.

In food production, lactic fermentation principally converts carbohydrates into lactic acid, plus (depending on conditions) acetic acid, carbon dioxide, and ethanol. The conversion makes the raw food more stable, digestible, and delicious. Notably, it also lowers the food’s pH, creating an acidic environment that’s inhospitable to spoilage organisms.

In other words, cooks use good bacteria to create conditions that prevent bad bacteria and other pathogens from ruining the food. In cuisine, we use LAB to acidify the product.

Bacterial fermentation in wine is a little different. Instead of using LAB to gobble carbohydrates, we use it for a different kind of transformation. In wine, we use LAB to de-acidify the product.

So, how does this bacterial process work in wine?

In wine, malolactic conversion is principally carried out by Oenococcus oeni. These bacteria arrive at the winery on grapes and vineyard matter, but winemakers can also inoculate their wine using a cultured strain. The bacteria chomp on malic acid, plus some sugars, turning it into lactic acid and energy they use for growth and metabolism. This is why technically the process is a conversion (of malic to lactic acid). The process, like yeast fermentation, also generates carbon dioxide. Here’s the formula, greatly simplified:

C4H6O5 → C3H6O3 + CO2

Malic acid → Lactic acid + Carbon dioxide

The input of the reaction, malic acid, is present in many fruits and vegetables, including grapes and apples; malum is Latin for “apple,” and Malus is the genus of shiny orb we are advised to ingest daily. Grapes from cooler climates, colder vintages, or early harvests have higher concentrations of malic acid. Although yeast also consume some malic acid, after primary fermentation, much of the malic remains in the wine. Malic acid has a tangy bite and green apple flavor.

Lactic acid is not present in large quantities in grapes, but as we’ve seen it’s abundant in products cultured with lactic acid bacteria. The yeasts of primary fermentation can also create a small amount of lactic acid. The name is a nod to dairy production (lac is Latin for “milk”). Lactic acid has a softer texture and milky essence.

Sometimes malolactic fermentation chews up all of the malic acid in the wine, and sometimes the conversion is arrested, or stalls, partway through. Maybe a few tanks of wine complete it while others don’t, so the finished wine contains a mix. That’s called partial malolactic.

In the end, though, there is less malic acid and more lactic acid, and since lactic acid is weaker, the process has reduced the wine’s acidity, or raised its pH. This gives the wine a softer mouthfeel — less sharp and tangy, more round and creamy. The net result is a shift in both the texture and flavor of the wine.

When does malolactic fermentation occur?

Many factors contribute to the timing of malolactic fermentation. Different strains of LAB thrive in different environments, given variables of temperature, pH, alcohol, nutrients, sulfite, other microbes, and more.

In historic (cold!) wine cellars, primary or yeast fermentation completes in the fall, then the wine sits in barrel or tank, inactive, until spring starts to warm the cellar. At that point the LAB rouse from their hibernation and go to work. Or don’t — it’s not a foregone conclusion. Some winemakers, in particular natural winemakers, allow the ambient LAB cultures to kick off malolactic, but others will inoculate with a commercial strain they know will thrive given their preferred timing, conditions, and flavor results.

Malo can also happen concurrently with yeast fermentation, but most commonly winemakers prefer to let it roll in tank or barrel after that has finished. That’s partly because yeast and bacteria both love sugar, and the competition doesn’t always create happy outcomes. But it does mean relying on LAB that can tolerate higher alcohol.

Malo is undesirable after bottling in part because that trapped carbon dioxide makes the wine prickly or spritzy. It can also lead to off-flavors. Unlike with kimchi or yogurt, there are no active bacterial cultures in a finished bottle of wine.

Winemakers can prevent or arrest malo altogether through chilling, sulfite addition, pH adjustments, or filtering.

How does malolactic fermentation alter the aroma and flavor of wine?

Neither malic nor lactic acid contributes much to a wine’s aromatics (you don’t smell them because they are not volatile; see Acidity in Wine), although as we’ve noted the process does mute that green-apple taste.

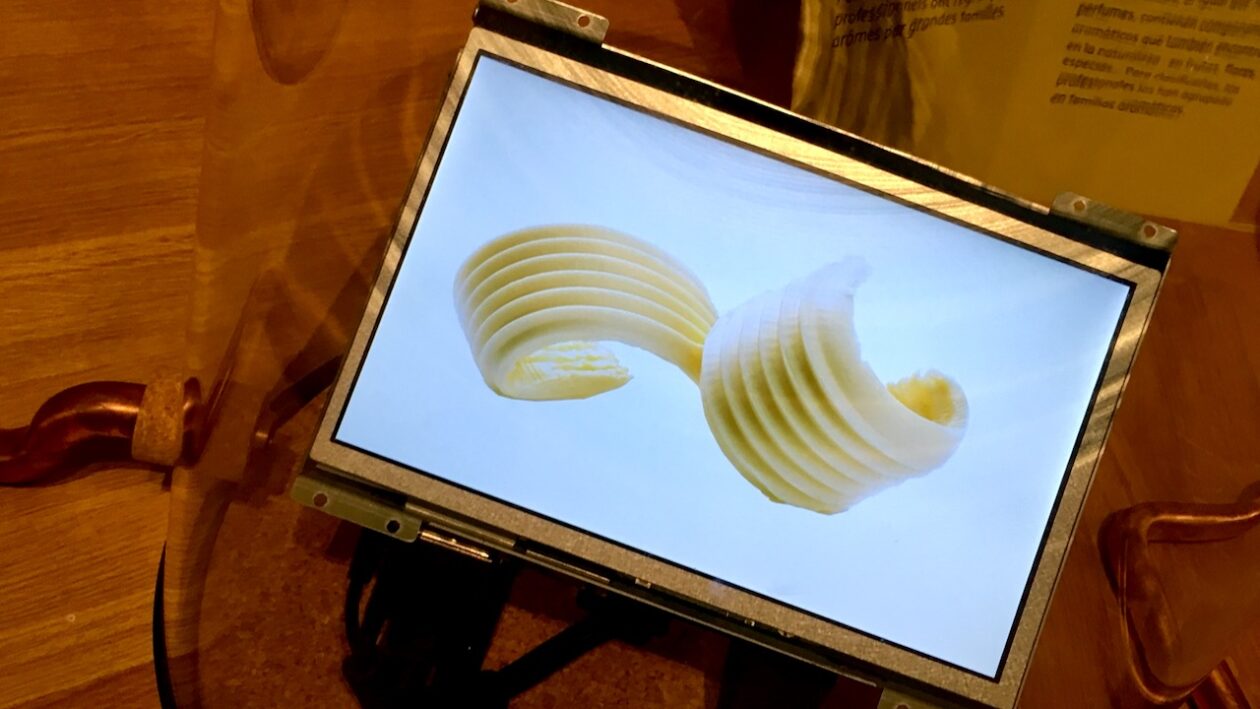

But malolactic also throws off flavorful byproducts that aren’t shown in the simple equation above. These include certain aromatic esters that deliver a panoply of pleasing fruity notes. Another byproduct, diacetyl, has a buttery flavor. Synthetic diacetyl is so potent it’s used as a flavoring agent for popcorn, margarine, and other foods. Different strains of the bacteria create different amounts of it.

Diacetyl gives white wines flavors of cream, butter, almond, and hazelnuts. It doesn’t make red wines smell buttery, per se, in part because the creaminess is masked by other aromas, and in part because malo acts somewhat differently on red wine’s chemistry. Malo has been shown to diminish fruitiness in some red wines, but it can also enhance spicy, toasty, and cocoa aromas, especially if it happens in oak barrels.

Malolactic fermentation can also go terribly awry, especially if unwanted LAB species elbow their way in, causing faults that make the wine rancid (too much diacetyl), mousy (like a rodent den), bitter, cloudy, slimy, or otherwise off-putting. Yuck.

Which wines go through malolactic fermentation?

Earlier I noted that “arguably the majority” of wines go through malolactic fermentation. That’s true, but the list is not arbitrary.

In red wines, malo is indeed nearly ubiquitous. Red wine benefits from the reduction in sharp malic acid; “tangy” and “green apple” are generally unfavorable descriptors for reds. The same is true for most orange wines, which are white wines made like reds, viz., allowed to macerate with their skins and seeds for extended periods.

Traditionally, white wines from cooler climates do go through malolactic. Those grapes are harvested with higher initial acidity and lower initial sugar, and they benefit from the softening step of malo. It’s historically prevalent in Chablis and the base wine for many cold-climate sparklers, for example, and is traditional for white Burgundies. Climate change is (chillingly) shifting many of these conventions.

Malo’s most famous application, some might say over-application, is in the ripe, buttery style of California Chardonnay that you might want to drink with a spoon. But as in Montrachet and other white Burgundy, that buttery quality can be brought into balance if the wine’s total acidity remains high and its pH low, and the élevage, especially conducted in oak barrels, manages to knit together the fruit, cream, toast, texture, and acidity into a balanced glass of wine.

Many natural winemakers choose not to intervene with their fermentations, yeast or bacterial; they do not inoculate with a lactic acid culture to kick off MLF, nor do they chill, filter, or sterilize the wine to prevent it. Because LAB are pervasive in the environment, this non-interventionist approach means that, generally speaking, most natural wines have gone through at least partial malolactic fermentation, regardless of whether they are red, white, rosé, orange, or sparkling. Proponents say the result is not only more natural but also more complex, with enchanting textural and flavor dimensions. And if it doesn’t happen, that’s okay, too. In short, natural winemakers take their cues from the microbes, not the other way around.

Which wines don’t go through malolactic fermentation?

Many white and rosé wines don’t go through malolactic. The outcome depends on stylistic and regional traditions, vintage variation, market aesthetics, and a winemaker’s personal taste.

In warm regions, malo is uncommon in whites, as the acidity can be low to begin with and the wine benefits from retaining its crisp edges. Assyrtiko, from sunny Santorini, is a good example of this. On the other hand, there are cool-climate whites that historically don’t go through malo, for example German Riesling, Austrian Grüner Veltliner, and Italian Pinot Grigio, even from the mountainous Dolomites. Tradition has set a certain flavor expectations (snappy, juicy, refreshing) for those varieties from those places.

In continental climates, for example Bordeaux and the Loire Valley, the white wine decision making is more complex. Some winemakers choose to suppress malo, for example in Sémillon and Sauvignon blanc. In the Loire, Chenin is often put through MLF (although not in Vouvray). Loire Sauvignon blancs may or may not go through it. Partial malolactic is another possibility; a winemaker may choose to allow malolactic in some vintages, or during a single vintage only in some tanks, blending the final result for balance.

Malo is generally uncommon for rosé wines, because youthful freshness and crunchy acidity are hallmarks of the style. However darker rosés, for example the “fourth wine style” of Tavel, often go through it, as does Rosé des Riceys. Also, many natural winemakers feel that allowing malolactic yields a richer, more dimensional rosé.

Actually, some red wines also don’t go through malo

In researching the world’s wines, I’ve bumped into some red styles for which MLF is rare or impossible.

The first is red port. In port winemaking, the primary or yeast fermentation is halted after one and a half to two days by the addition of a potent grape spirit (essentially un-aged brandy). This process, called mutage, raises the alcohol level to 20%, killing yeasts and bacteria. This renders it stable, viz., inhospitable to microbial growth despite high residual sugar. On my visit to Symington port properties in 2019, winemaker Henry Shotton confirmed that malo is suppressed, but that the 100 to 110 g/L of residual sugar smooths the wine’s malic acid as well as its tannins.

Another curious exception is Amarone, a wine made from dried grapes. On a 2019 visit to Santi’s grape drying warehouse (called a fruttaio), I noticed a large research poster on the wall outlining data they’d collected on the trajectory of sugar and acidity in the grapes during the 90 days of pre-vinification drying. My host, cellar master Christian Ridolfi, explained that as moisture drops in the berries, the sugar and acidity rise, but malic acid actually falls — from 3.0 g/L to 0.5 g/L. Hence, 90% percent of the lots do not go through malo (and if some lots do, it’s fine with him). The finished wines have a pH of 3.3 to 3.4, which is not too tart, not too soft. Just right.

Finally, for wines that have been treated to full carbonic maceration — Beaujolais is the classic example, although it’s used elsewhere, too — malo may be reduced or even preferentially eliminated. The intercellular, anaerobic process of carbonic maceration eats up malic acid, so a subsequent malolactic fermentation can lower the wine’s acidity too much. Also, in the absence of malic acid, LAB may go to work on leftover sugars, which can create those off-flavors and faults mentioned above. On the other hand, speeding through carbonic, yeast, and MLF fermentations allows producers of Beaujolais Nouveau to press a “finished” wine into consumers’ hands by the middle of November.

Malo, or not, in your glass

If you’ve gotten this far, you’re probably wondering how to translate this information into news you can use.

When popping open a red wine, know that except if it’s a fortified or dried grape wine, or a fully carbonic Gamay, or another real oddball (Heitz Cellar famously suppresses malo in its Cabernet Sauvignon), you’re almost certainly tasting the results of two processes: yeast and bacterial.

At the other end of the scale, most rosé is malo-free. Unless you’re ordering pink wine in a natural wine bar, or hanging out with vignerons in tiny Riceys, you’re probably drinking the product of a single fermentation (by yeast).

For other wines, it’s a mixed bag. Labels rarely mention malolactic, and while some whites may say “unoaked,” that’s a different issue. As we’ve seen, certain regions and wine styles have malo baked in, but in places with looser laws and customs, winemakers may choose to, say, put a rosé through it or suppress it in a red.

So what about that butter? Since the flavor can be galvanizing, it’s useful to learn what works for you, so try the exercise below. My best advice is to brush up on regional style, taste broadly, make notes of what you love — and ignore wine snobs proclaiming any style to be démodé.

Try This at Home

Round up eight or ten Chardonnays with different malolactic protocols, optimally made in different regions and following differing winemaking philosophies. (Ask your favorite wine merchant for help with this exercise.)

Pour these as a flight, ideally from non-malolactic to fully malolactic. Note how some feel crackly and sharp while others are satiny. Look for the difference in flavor, too, ranging from tart fruit to cream to custard. Do the richer wines feel balanced? What about the sharper wines? Which wines would you drink by the glass (if any)? Which foods would you reach for with these different wines, and why?

Images from the Cité du Vin, Bordeaux, photographed by the author in July 2016 and June 2019. Many thanks to enologist Kryss Speegle MW for her expert review of this article.

Nice work, Meg. I’ve been doing a little research on why Chablis doesn’t show the butter notes even though it does go through Malolactic conversion. Do you have any leads on answers to this one? I know timing is involved, and some LAB create more diacetyl than others, but nothing definitive. Thanks!

Jeff, thank you. I don’t have specifics to point to except that I believe Chablis has high malic to begin with. I also understand that, as you say, the different strains of LAB have different outcomes vis a vis diacetyl. I will do some research and write back as I know more. Thank you for reading! Cheers, Meg

Well done Meg. When you discuss comparing wines with and without MLF I always think of the Hyde Chardonnays from Ramey and Massican. Two very different approaches to the same grape & same place. Can’t say I like one more than the other, except that Dan’s is considerably less expensive!

Thank you, David. I love that example! For readers who aren’t familiar with these wines, Dan Petroski, winemaker at Massican, doesn’t let his Hyde Vineyard Chardonnay go through malo, while David Ramey, of Ramey Wine Cellars, puts that same fruit through full malo (using ambient cultures). This A/B test would set you back $145, plus shipping, so it would be a pricey, if worthy, way to test one’s tastes.