Acid means refreshment. Think about biting into a crisp apple, a ripe lemon, a slice of pineapple. The acidity of the fruit feels stimulating and juicy. In the same vein, our most popular beverages are also acidic. Consider tea, coffee, orange juice, apple juice, soda, beer, wine. (Milk not so much, unless it’s been fermented.)

The acidity of these drinks is an essential characteristic, because it cleanses our palates with each sip. A wine without sufficient acidity will taste flabby and dull.

Acidity is critical to the enjoyment of wine, but it’s also essential to the production of wine. The character of a wine’s acidity determines how it ferments, ages, and behaves in bottle in the long haul. It helps determine its fate.

It Starts With The Fruit

Wine’s acidity originates in grapes, but acid is also created during winemaking and aging.

Different grape varieties have varying amounts of acidity: Chardonnay, Albariño, Chenin blanc, and Colombard are examples of white grapes high in acid; Pineau d’Aunis, Schioppettino, and Nero d’Avola are some high-acid reds.

Vine growers labor to preserve acidity as the season progresses. Warm climates, hot weather, and heat spikes can throw the balance of sugar and acidity out of whack. That leads to problems in the cellar, because musts with lower acidity are more susceptible to spoilage organisms and other problems. Managing grape acidity is a key concern for growers given our warming climate.

A Healthy Mix of Acids

All finished wines contain a mix of different acids, each contributing something to the wine’s aromas, flavors, and textures. Adding to the naturally occurring acids are some produced during winemaking, by both alcoholic (yeast) and malolactic (bacterial) fermentations. Together, these acids help balance a wine’s sweetness, fruits, tannins, and texture, and participate in its aging trajectory.

Acidity in wine is reported using two measures: pH and TA.

The pH, or concentration of acidity in the wine, generally falls between 3.0 and 3.8. White wines have lower pH, usually in the range of 3.0 to 3.3, while red wines fall between 3.4 and 3.8. Wines above that range often feel flabby and unbalanced, while wines below it feel sharp and sour.

The TA, for total acidity or titratable acidity, is a measure of the volume of acid in the wine, which is reported in grams per liter. Modern enologists single out a single acid for evaluation, tartaric (watch the process here). Finished wines have between 4 and 9 g/L of acid, with a range of 5 to 7 g/L most common.

Wine’s Fixed Acids

The bulk of the acidity in wine derives from five fixed or stable acids, so-called by chemists because they don’t evaporate when heated. They are not volatile, so we don’t smell them, but we can taste them and feel their effects on our tongues. These acids are tartaric, malic, lactic, citric, and succinic:

- Tartaric acid is the most abundant acid in wine grapes and plays a crucial role in stabilizing a wine and helping it age well. Winemakers may add tartaric acid to fermenting wine if the must is insufficiently acidic. As a bottle ages, some tartaric may eventually precipitate out, leaving harmless wine-stained crystals around the punt and on the cork. Tartaric acid similarly builds up on the insides of aging casks in the maker’s cellar, and these tangy scrapings are used as a naturally-derived leavening agent in baking — the original cream of tartar.

- Malic acid is also abundant in grapes and other berry fruits. It’s susceptible to temperature and other climatic fluctuations during the growing season (tartaric is more stable). Malic may also be added by winemakers to adjust the pH of the must. Malic acid gives wine a green-apple tang, which is desirable in crisp white wines (hello, Pinot grigio!), but less so in reds. That’s why nearly all red wines, and some white wines, go through the transformation of malolactic fermentation (MLF), in which lactic acid bacteria convert the malic acid into softer, gentler lactic acid.

- Lactic acid is generally not present in grapes, but can be produced if the fruit becomes bruised or damaged. Lactic acid is also present in fermented dairy products, so when, for example, you taste a Chardonnay that has gone through malolactic fermentation, you can sense the same kind of creaminess. (You’re less likely to notice this in red wines that have gone through MLF simply because it’s obscured by the other aromas and flavors.) Allowing, or preventing, malolactic conversion is an important stylistic decision for makers of white wines.

- Citric acid is familiar to many because it exerts a strong presence in globally popular citrus fruits like lemons, limes, and oranges. But it’s also abundant in many other fruits and vegetables, delivering a sour taste we generally find tart and pleasant. Although naturally present in grapes, it can also be created by fermentation yeasts.

- Succinic acid isn’t present in grapes, but small quantities can be created during alcoholic fermentation. It has a fairly neutral, sour-astringent impact on the taste of wine.

Wine’s Volatile Acids

The remaining acids in wine are the volatile acids, and they’re present in far smaller quantities. There are eight in all: acetic, butyric, isobutyric, propionic, hexanoic, sorbic, and sulfurous. Because they’re volatile we can smell them.

Of these, acetic is by far the most abundant, while the others are rarely present in volumes detectable by the human nose. That means that when we talk about “volatile acidity,” or VA, in wine, we’re essentially talking about acetic acid.

Acetic is a natural byproduct of alcoholic fermentation. You can’t make wine without making some acetic acid. Yes, this is the acid of vinegar, which gives it a bad rap vis à vis wine. But in the case of vinegar it’s present at concentrations of 30 to 90 g/L, versus only about 1 g/L in wine. (Vinegar’s pH is also far lower, usually around 2.5.) Acetic concentrations in wine above 1.4 or 1.5 g/L will seem unacceptably vinegary. A little goes a long way.

You can’t make wine without making acetic acid.

Acetic acid can also be produced by spoilage organisms, specifically acetic acid bacteria (Acetobacteraceae) and undesirable yeasts like Brettanomyces. Fruit flies are a common vector for acetic acid bacteria, and if you’ve ever been in a winery at harvest, you know that these little bug(gers) are abundant everywhere; managing them is a critical aspect of vineyard and winery hygiene.

Acetic acid is even sometimes present in the wood of new oak barrels and can leach into the wine during cask aging. Also, too much oxygen can accelerate the production of acetic acid. Wines in bottle, having aged past their prime, due to too much time in the consumer’s cellar, or simply a flawed cork, will earn an oversupply of the stuff, rendering them sharp and fruitless and generally unpleasant.

Some say that vinegar is the fate of all wine.

Volatile Acidity: Faulty or “lifted?”

Although excessive acetic in wine is considered a fault, a little can add character and nerve — a brightness some commentators describe as “lifted.”

Sometimes this is even considered characteristic of a regional style. Many Italian red wines aged for a long time in oak casks, which exposes them to oxygen, earn a light vinegar aroma that tasters charitably call a “balsamic” note. It’s so common that it’s not considered a fault unless it’s utterly out of balance with the rest of the wine’s elements: fruit, tannin, texture, wood, and all the other qualities that make — well, a Chianti a Chianti, or a Barolo a Barolo.

Sweet wines also frequently exhibit high levels of VA, which is often coupled with another volatile compound, ethyl acetate. That one-two punch gives the wines a sharp, vaporous quality which can be off-putting, but again, at lower quantities they give welcome lift to such a sugary wine.

Truly, it’s all about balance.

Try This At Home

Below is an experiment to simulate the impact of acetic acid on wine. You’ll need two identical wine glasses, a neutral tasting white wine like Pinot grigio, and white wine vinegar. The adventurous will also want a red wine and red wine vinegar.

First, pour an ounce (30 ml) of wine into each glass. To one glass, add ¼ teaspoon (1–2 ml) of white wine vinegar and swirl to incorporate. Sniff the un-adulterated wine, then the one with vinegar. Then taste in the same order.

Reflect on the differences. Does the vinegar present to you more as aroma or flavor or tactile sensation? How does the vinegar change the texture of the wine? How would you describe the overall effect: is the wine “lifted” or just spoiled?

You can repeat this exercise with a dry structured red wine like Chianti Classico, or really any red wine you have on hand. In this case, use red wine vinegar or aged balsamic instead of white wine vinegar. Does the vinegar have a different effect on the red wine than on the white wine? Is it more or less pleasing? More or less interesting?

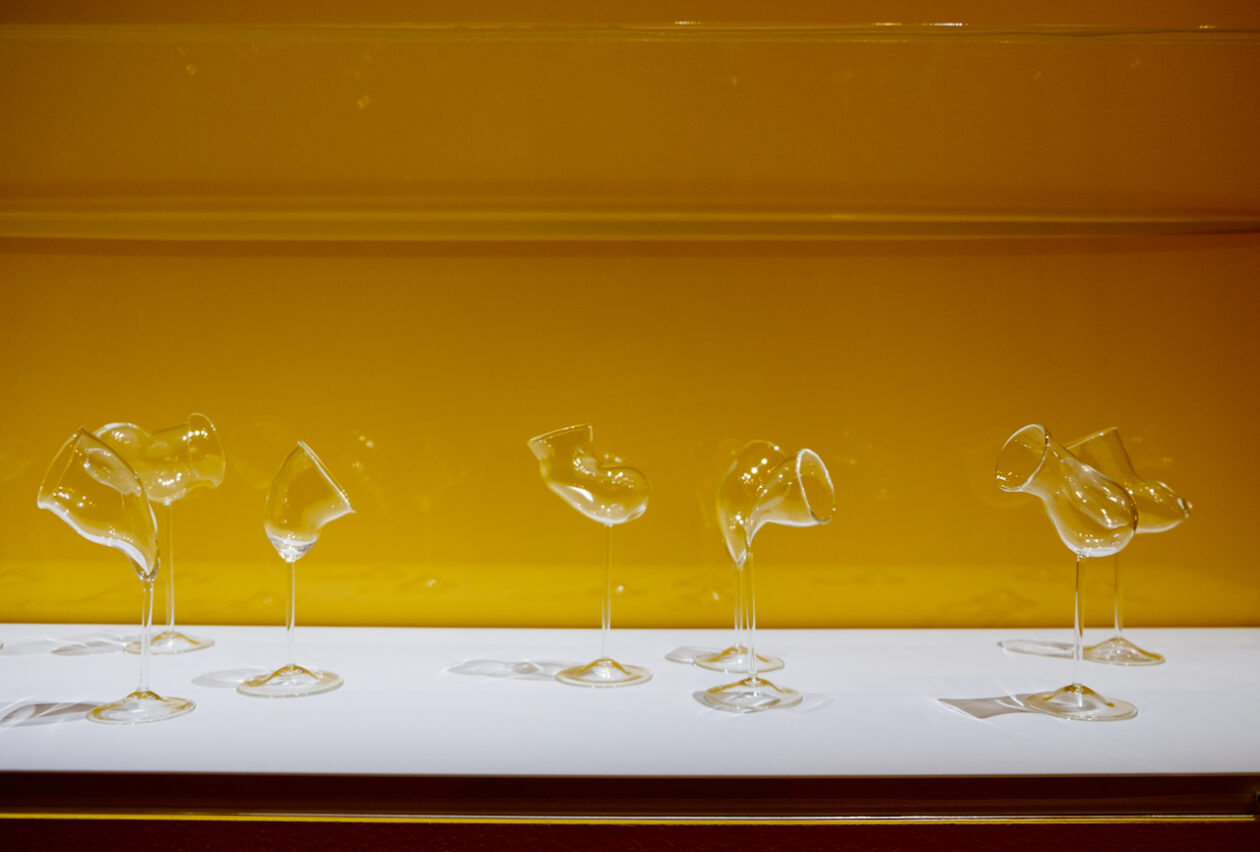

Images from the exhibition Renversant! Quand Art et Design S’Emparent du Verre at the Cité du Vin, Bordeaux, photographed by the author in June 2019.

Ed. note: An earlier acidity primer I published elsewhere was part of a series selected as finalist for the 2022 IACP Food Writing Awards / Beverage Focused Column.