Maps partition culture into here and there: These people here, those people there. We allow for some blending in the middle, perhaps, the hyphenated elision of Here-There, This-That. But it’s easy to conflate map and territory: People here are like this, people there are like that.

Looking at a geopolitical map of southern Europe, you find a heavy line meandering along the Pyrenees from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, separating France from Spain, with a loop like a needle’s eye around Andorra, and that curious slipknot Spanish exclave, Llívia.

Looking at a linguistic map of southern Europe, you find different boundaries. The names of the zones are different—Occitan, Aragonese, Basque, Castilian, French, Catalan—language features traced by lines linguists call isoglosses: This language here, that language there.

The geopolitical map’s demarcations are governmental distinctions, more about commerce and taxes than culture, language, habit, faith, attitude. The linguistic map, meanwhile, describes older loyalties, deeper and more heartfelt. Language is culture, culture transcends politics.

“I’m not Spanish. I’m Catalan,” a winemaker said to me recently in Penedès. I instantly recognized my mistake, having constructed a remark from geopolitics, not culture. I should have known better. Driving through that rural region, I’d seen many house windows draped in the pro-independence Catalan flag, with its red and yellow stripes of unity, and its starred triangle of separation. This region is not Spain, exactly, or not only Spain. These people are not only This.

Just to the north, over the Pyrenees, lies Roussillon. The territory was warred over by Aragon and Majorca, Spain and France, until it became become part of France in 1659 with the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees. It is administered as the French département Pyrénées-Orientales, but by heritage it remains Catalonian. It’s equally known as Northern Catalonia—Catalunya Nord in Catalan, Catalogne Nord in French. Its people are tethered to a broad swath of land reaching south across the Pyrenees—crossing a line no one sees from space—down the coast to Valencia, east to the Balearic Islands, and farther eastward even still to a tiny sliver of land in western Sardinia.

The language of Roussillon, too, like its heritage, is officially French but authentically Catalan. Although the tongue was banned for centuries, more recently it has been allowed in schools, and a quarter of the population now speaks, and far more understand, Catalan. In neighboring Languedoc, meanwhile, to Roussillon’s north and east, the heritage language is Occitan (whence the name: langue d’oc). On the linguistic map, Occitan reaches north roughly to Bordeaux, curves east atop the Massif Central, spreads east and south to the Rhône, Provence, and into Piedmont. Catalan is here. Occitan is there.

It’s also cut crosswise by three rivers flowing from massif to Mediterranean—l’Agly, la Têt, and le Tech. Over eons this fluvial drainage system has sliced through layers of metamorphic rock and sedimentary soils to form terraces: crumbled, stratified mélanges of limestone, schist, clay, gravel, sand, and stones. The higher terraces are less rich, the lower terraces more so, and adding slope and aspect yields a rich diversity of growing conditions. This soil here, that soil there.

Such micro-terroirs have given rise to fourteen separate wine appellations, including four village-level AOPs. Red grapes anchored to these soils include Grenache, Carignan, Syrah, and Mourvèdre; whites include Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, Muscat of Alexandria, Grenache Blanc, and—its tendrils linking it to Catalonia, where it adds a floral lift to Cava—Macabeu.

Vin Doux Naturel was invented here in the late thirteenth century. It’s made by adding grape spirit during fermentation (a process called mutage) to produce sweet, fortified wines in styles either young or oxidative—called tuilé for whites made from Muscat, and rancio for reds made from Grenache.

Roussillon’s dry wines are traditionally blended, each variety’s personality contributing something to the wine’s countenance: Syrah for spine, Mourvèdre for muscle, Carignan for heart, Grenache for blush in the cheek. AOP regulations stipulate not only the required varieties but also minimum and maximum percentages. Maury Sec, for example, (tasted below) must contain at least two black varieties, with Grenache between 60 and 80 percent of the blend, and Lladoner Pelut, if used, no more than ten.

Such rules might seem arbitrary—This in, That out—but their aim is to codify tradition. Their aim is also ennoblement, elevating the region by eliminating methods deemed déclassé. Roussillon’s historical over-cropping might be considered in some sense “traditional,” but it engendered a reputation as the wellspring of the European wine lake. Lowering yields to 32 hectoliters per hectare (the French average is 60), has boosted quality.

I have not visited Roussillon (although it might be time), but I have visited the Languedoc. When I asked winemakers there about their regions, I never heard them mention Languedoc-Roussillon. They hardly even mentioned Languedoc. They spoke instead of their own appellations, their own locales: Corbières, Faugères, Minervois, Saint-Chinian, La Clape. These are as different in their minds as Spain and France. Maybe even Mars and Moon.

The map is not the terroir. Wine is always local, always a lens of culture: this place, this vineyard, this grape, this grower, this heritage. And so when we conjoin by hyphen Languedoc-Roussillon (then prop it under a marketing banner, Sud de France) we let slip the thread of character. We lose the distinctiveness of Here and There, This and That, and deprive ourselves of a vital difference that might inform our thirst.

TASTING NOTES

The following six wines from Roussillon were presented at a recent tasting organized by Snooth Media and led by sommelier Caleb Ganzer of Compagnie des Vins Surnaturels, a wine bar in New York City. They represent a tiny sliver of the region’s offerings, the promises it makes.

2014 Michel Chapoutier Les Vignes de Bila-Haut Côtes du Roussillon

A blend of Grenache Blanc, Grenache Gris, and Macabeu, grown in limestone clay in the Têt river valley. Harvest was manual, and the wine was fermented and raised in stainless tank. The scent mingles wet stone with white flowers, and the body is floral, too, with demure yellow melon and a lovely herbal breath at the finish. This is a terrific picnic wine, a cheese wine, great for sandwiches, salads, plein air. Although I don’t generally don’t recommend serving still white wines very cold, I like this one with a deep chill because it quiets the flowers and lets the essence of field and stone and sunlight shine out.

13% abv | $16 (sample) Imported by H.B. Wine Merchants

2011 Gérard Bertrand Grand Terroir Côtes du Roussillon Village Tautavel

Tautavel is one of four village sub-appellations within Côtes du Roussillon, and throughout the region, the reds are mandated to be blends. This wine is half Grenache, with the balance Syrah and Carignan, grown in limestone clay soils. The varieties were vinified separately, then aged ten months in barrels. It offers a fragrance of sweet red raspberries and warm red apple skin, then gets more serious on the palate, which is peppery with a medium grip and a hint of coffee at the finish. A filigree of resinous herbs adds interest, as does the bottle age, which has burnished its body a garnet color. Overall a ripe but well structured wine that would be great with grilled and charred meats. It’s somewhat reminiscent of Argentinian Malbec, for that reason—fruit notes to contrast with the char, and tannins to complement it. Great for picnics, steaks, barbecue.

15% abv | $18 (sample) Imported by USA Wine West

2013 Vignobles Jaubert et Noury Château Planères La Romanie Côtes du Roussillon Village Les Aspres

Les Aspres is another of the village sub-appellations, and this wine is half Syrah with a complement of Mourvèdre and Grenache. The fruit was grown at high elevation in the Albères mountains, in clay and gravel with limestone sub-soils. Harvest was manual, and the must macerated for thirty days, with pump-over, after which the wine reposed in new French oak for twelve months. The aromas are sweet, with candied red fruits and stewed blueberries, but the wine darkens as you step inside it, suggesting a blackberry bitterness with a departing flare of juniper and pine. There is a cooling middle note carried on an ample armature of acid and tannin—the likely result of that fervid vinification and aging. Its structure and serious center make it read somewhat like a Bordeaux, but with mountain air freshness. Youthful, tight, and muscular now, bottle age will smooth and unify it.

13% abv | $25 (sample) Imported by The Wine Source, Inc.

2013 Domaine Cabirau Serge et Nicolas Maury Sec

The Maury appellation has long been associated with Vin Doux Naturel, but with the 2011 vintage, the Maury Sec AOP was approved for dry red wines. These by law must be Grenache-dominant, and this one is 60 percent Grenache from 60-year-old vines, with a balance of Syrah and Carignan. Harvest for all fruit was manual, and while the Grenache was un-oaked, the other lots were aged five months in 500-liter demi-muid casks. The wine evinces scent of red fruits steeped in resinous herbs and juniper berries, and it’s woodsy on the tongue, with an exuberant tannic presence and big, chewy structure complementing earthy notes of cedar and tobacco. The fruit here is all black: black plums, black currant, blackberries—especially evoking the astringent blackberry seeds. Many people shy from bitter, but bitterness in wine is vitalizing.

14.5% abv | $26 (sample) Imported by Hand Picked Selections

2011 Domaine Cazes Muscat de Rivesaltes Vin Doux Naturel

A fifty-fifty blend of Muscat of Alexandria and Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, organically and biodynamically grown in limestone clay soils littered with galets, rounded stones the size of softballs (even footballs) not uncommon in southern France. The wine was fortified halfway through fermentation, with some lots continuing maceration afterward for color and flavor extraction. The wine is a lovely amber gold color, with sweet Muscat notes—paper whites, lily of the valley, jasmine, ripe white peach, apricot—plus marzipan or hazelnut. It’s volatile, too, though, unctuous and syrupy textured, the body suggesting silken apricot, almond, and white tea. Serve it cold, with a cheese course.

15.5% abv | $15 (sample) Imported by Robert Kacher Selections

2014 Domaine la Tour Vieille Banyuls Rimage

Banyuls is perhaps better known for oxidative styles (rancio), but Banyuls Rimage, made only in good vintage years, undergoes long maceration after mutage (spirit addition) and then is bottled younger, preserving fruitiness. In this case, the maceration of the Grenache and Carignan continued for three weeks after fortification to extract phenolics and color. The wine was then foot-pressed, pumped back into the vats, and held full to prevent oxidation. A deep black ruby color, it’s demure at first, with a quite nose of black cherries and plums. But its flavor is an embroidered tapestry of acid, alcohol, tannin, fruit, earth, all in beautiful balance. It’s rare to taste a wine that’s both bitter and sweet (or for that matter, anything that’s both bitter and sweet); a mix of black and red and black again. Pour this wine as you would a ruby Port. It loves salt and richness: blue cheeses, aged Gouda, salted nuts. Or, dessert: chocolate, mocha, cherry torte. And while you’re at it, try to imagine how many tours vieilles you might find in this corner of the world.

15.5% abv | $30 (sample) Imported by Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant

Coda: Tasting wine is like a tour bus ride. When you get off the main road, get out of the van, and look closely, there is much to see.

Many thanks to Wine Business and Wine Industry Insight for recommending this article to their readers.

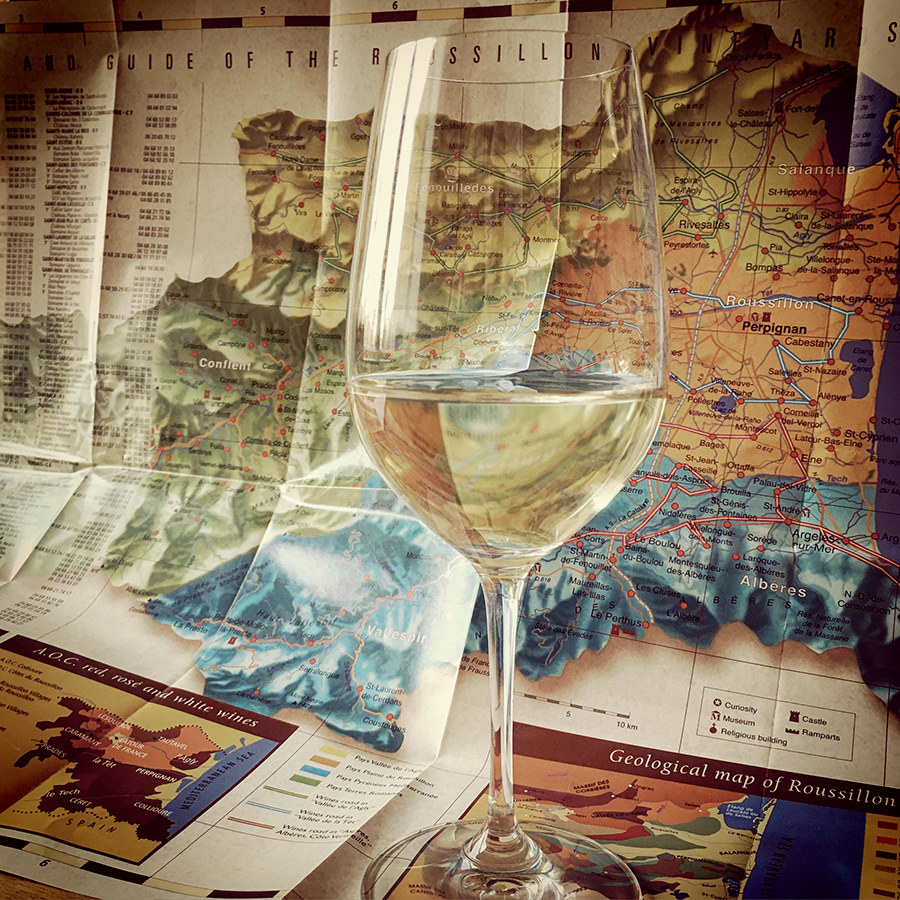

Map at top by Conseil Interprofessionel des Vins du Roussillon; map at center by De Long.

All wines were media samples for review. I was compensated to participate in this tasting. View my Sample and Travel Policy.

Follow me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Thank you Meg. That was an engaging read on an area I know too little about.

I saw your mention of organic/biodynamic in one of the notes. Is more sustainable agriculture making serious inroads in any of the areas?

Hi David. Thank you, as always, for reading.

Sustainable, biodynamic, and organic viticulture does have a toehold in this region, as well as in the Languedoc and in southern Spain. It’s much easier to farm organically when disease pressure is low, and given long periods of hot, dry weather, continuous winds, low soil moisture, and many hours of sunshine, vignerons can get away with minimal or no interventions.

However, of those who farm this way, only a portion will go to the trouble and expense of certification, which leaves them free to resort to additives when absolutely necessary to ensure the crop. This is why you won’t always see “organic” or “bio” on the label, even when the juice inside is from organic sources.