I delivered the following remarks to a plenary session concluding the Wine Bloggers Conference in Corning, New York, on 16 August 2015. I introduced the talk by saying, simply, “Because I’m a writer, I wrote something for you. I wrote this for you.”

You have a wine blog. Congratulations: You are now a nonfiction writer.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t tell a story. In fact, you must tell a story if you want your work to be read, and if you want your reader to keep reading.

Good wine writing demands more than just a palate and a vocabulary. It demands curiosity, creativity, insight, and diligence—and that’s true whether you approach your work journalistically or view your blog as a strictly artistic endeavor.

Good writing is also about more than grammar and syntax. These reside squarely in the realm of copy editing. This is writing writ small.

I’m speaking here about the realm of storytelling, of story doctoring, the art of stitching your piece together into something that is bigger than the sum of its parts. Something that says something you believe to be true.

If you’re willing to master a few techniques of good writing, you can keep your reader reading. These techniques aren’t hard, but they do require you to bring your writing to a level of consciousness: To inquire, to listen, to reflect, to syncretize—to tell a story.

On Friday during her keynote, Karen MacNeil told us that blogging is about speed, and that “with speed comes a great responsibility. Don’t ‘throw up.’ Say something clever. Be clever about capturing an idea fast.”

There’s a lot of wisdom there, but I don’t believe blogging is necessarily about speed. Speed is characteristic, but it is not essential. You can take your time. Research. Reflect. And apply your own perspective on the material, your own knowledge from experience—your expertise.

As a nonfiction writer, you are a proxy for the reader. The reader relies on you to ask the questions she would ask if she were the one tasting with the producer, or walking with him in his vineyard, or stomping his grapes with him, your pant legs rolled up, your calves purpled. Have you ever listened to Terry Gross, who hosts the radio interview program Fresh Air? She asks the questions you’re thinking before you even know you’re thinking them. That’s good interviewing.

If you want to be a good nonfiction writer—if you want to be a better nonfiction writer—you must read good nonfiction writing. Read food and wine writing, both in periodical and book form, but don’t only read food and wine writing. Read the New Yorker. Read the Atlantic. Buy new nonfiction books about almost anything and read them, and while you’re reading, look at how the writer—and, let’s be fair, the editors—are stitching the narrative together.

Above all, pay attention to how the culture is talking about itself, because as a writer, your voice is part of that conversation.

So—on to those techniques, the skills that can help you tell a powerful story whether you’re writing about one wine or a hundred, one producer or a whole region. This list is incomplete, but it is a good place to start.

First, Prepare. Conduct research prior to the tasting or producer visit. This will help you formulate good questions. Notice any gaps in your reading. What are you curious or confused about? During the interview, ask those questions and any others that arise. Pursue your curiosity. Afterward, you’ll probably need to do more research. This will help you understand some of the things the producer said; when in doubt, you can follow up for clarification.

Research is a fundamental idea, but it is often skipped.

But—this doesn’t mean you have to become an expert to write one 1,000-word piece. You just have to have an understanding of something, some idea, that’s worthy of sharing with readers.

Relatedly, and partly because it’s a blog, it’s okay to write about stuff you don’t fully understand—it’s just not okay to pretend that you do. You can admit your struggle, and let your reader join you in it. Let them know why you care about it and what you’re doing to learn more about it. Ask for comments that can help your thinking. You don’t have to have all the answers, but you do have to have good questions.

Second, Listen. You are asking questions, so listen to the producer, the sommelier, the restaurateur—whomever you’re interviewing. Listen closely. Write down what he says, and also record him. Get the audio transcribed and, if necessary, translated. Read the transcript.

There are two good reasons for listening closely. First, because it will help you develop new questions during the interview. Your subject will say something that sparks an idea, and you’ll want to pursue that idea.

Second, because there is no substitute for your subject’s actual voice—her syntax, tone, color, style. Listening helps you keep from paraphrasing, so that you don’t write, “I asked the producer why she started to make skin-contact whites and she told me that since she’d been making red wine for years in Napa Valley she thought it would be fun to try working that way with white grapes.” Blah, blah, blah.

First, it’s a mouthful; syntactically it’s horrendous. Second, and most importantly, that’s not her voice, it’s yours. Your story is about her, not you. Listening, and quoting your subject, is a form of deep respect. It’s also more interesting.

Here’s a better approach: I asked her why she makes skin-contact whites. She said, “Because I also make Napa Cab.” Now that’s interesting. It’s provocative. It leads to other questions. And it makes your reader want to keep reading.

Okay, you’ve done your research, completed your interview, done the tasting, and now you must write. How to start?

Consider audience. Whom are you’re writing this story for? Consumers, or trade? New consumers, or experienced consumers? People who know what qvevri are, or people who think Clos du Bois must be better than Yellow Tail because it sounds French? If trade, are they in production or service? On-premise or off? International or local? Knowing your audience will help you structure your piece, decide what to keep and what to toss, what’s relevant to the storytelling and to the reader’s understanding.

Regardless of who your audience is, you must always assume limitless intelligence but limited prior knowledge of your subject today. It’s not insulting to toss a parenthetical about qvevri into your article on Pheasant’s Tears. Novices will be grateful. Experts will gloss over it, while being impressed that you’ve done the journalistic right thing and explained the jargon. And don’t you want a grateful, impressed audience?

As I said earlier, readers like stories. The late British writer Angela Carter once said, “Storytelling came before reading and writing, and will probably last after it.” We all crave stories. Stories are how we make sense of the world. We tell stories to each other to make the facts of reality cohesive, to make them understandable and memorable.

What are the elements of story? At the most fundamental level, a story starts in one place and ends in another. This is often referred to as a narrative arc. Something has changed over the course of the piece. It’s your job as a writer to figure out what has changed, and why, and to help your reader navigate that story arc, to move her to that other place.

If your piece were a fiction story, it would have a hero, a goal, and obstacles. Battling those obstacles is the stuff of true drama. It’s what keeps the reader reading. It’s sometimes interesting to think of your wine article this way. Who is the hero? Or what is the hero? It isn’t always the winemaker. It might be the wine, the region, or something else entirely. What’s in the way? What are the obstacles for this hero? How does the hero battle those to get to the goal?

Take a cue from playwriting: Start your story in the middle of the action. The great screenwriter Billy Wilder once said, “An actor enters through a door, you’ve got nothing. But if he enters through a window, you’ve got a situation.”

Start with a situation. Maybe it’s a provocative quote, a surprising taste, a conflict or argument, a circumstance of frisson or confusion. Starting this way will snap your reader to attention. Then, keep moving. Use active verbs, powerful verbs, to keep the reader moving.

Relatedly, chronology is a reasonable organizing principle for a train schedule. It is possibly the most boring organizing principle for a piece of writing. Find a way to play with time. You tasted the wine before interviewing the principal? You can still start with a quote from the principal. Start in the middle of the action.

These same techniques apply to journalistic writing, too, just with a slight shift in emphasis. Journalistic pieces must have a lede. That’s a provocative line or two at the top that’s a hint about what the story is about, but mostly it hooks the reader. Journalistic pieces must also have a kicker. That’s a provocative line at the bottom that summarizes the piece and (often) puts a wry twist on it.

Journalists can be most themselves in the lede and the kicker. This is (journalistically) where the writer gets to show her hand. It’s where personality and perspective come out. If you’re writing for a publication where you have to say, “a visitor” instead of “I,” then you’ll want to think especially carefully about your lede and kicker.

Regardless of whether you’re writing journalistically or more creatively, remember that as a wine writer, you’re writing about a sensorial—a sensual—product. So, switch on your reader, wake up his body. Use words from the wine domain that have palate texture: taste, clink, spit, slurp, lick, liquid, delectable; but also words from outside of the domain that reinforce these sounds: loquacious, picket, ticket, rattle, slice. Do this early in the piece, too, to activate your reader’s sensorium. Try to make him salivate.

At the very heart of the piece is your true story. Every story operates on at least two levels. First, there is a surface narrative. This is what your story is about at the level of topic. The particulars about the winemaker and region, the details about your trip, what you saw and tasted. This is the level of description. Far too many wine articles fail to move beyond the level description. Description is important, but it does not a story make.

Every piece also has something below the surface narrative. This is the what-it’s-aboutness that lives at the level of true meaning. This is the heart of the story, and you must look for it as you’re writing. You must find this, because your reader is looking for it, and if you don’t know where it is, he sure won’t.

Even a simple wine review should go beyond surface narrative—cherries, brambles, grippy tannins. Why is the wine truly interesting? What makes it different and special in the pantheon of all wines, wines of this style, of this type, of this producer? This sub-narrative doesn’t need to be expansive, but it has to show that you’re thinking, not just recording your sensations. It has to reveal what’s in your mind about the wine, so you can get that idea into the reader’s mind.

You have a first draft done. Okay, now type out this question: “What is this piece about?” Then type the answer. Or ask a friend to ask you the question, then answer your friend. You must be able to answer this question. If you can’t answer it, then nobody can—and certainly not your reader. Keep writing until you can answer that question.

My last piece of advice is simply this: Tell the story only you can tell. You did the research, you talked with people, you tasted the wines. You now have a view that matters, because it’s your view, it’s unique, and it deserves to be shared. It’s not, What would a Famous Wine Writer say about this material, it’s What do I have to say about it? Why does this story matter? Why is this story worth telling? Why do you think it’s worth telling?

Be choosy about what you write about. You only have one life. And you only have a handful of readers, cosmically speaking. They are precious, they are solid gold. Don’t try their patience with stories that don’t really need to be told. Remember, readers must read every word you write. Tell them a story—one you want to tell, and one they want to hear.

Many thanks to Wine Business Monthly and Wine Industry Insight for recommending this article to their readers.

Follow me on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Delectable.

“What is this piece about?” Then type the answer.

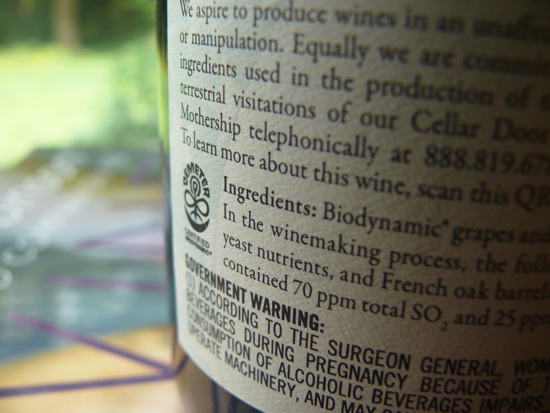

I was given similar advice about photography: What do you want to say with the image? If you don’t know, put the camera down. You are going to take a snapshot, not a photograph.

Meg,

This is such a thoughtful piece. You have a true talent with words and for doing the research that informs the content — the quotes from Carter and Wilder are fabulous.

Dixie Huey

Robbin and Dixie, thanks so much for reading and for contributing your remarks.

Meg, in fine writing style you conveyed your wisdom and experience in a very personal way. Hearing you deliver this essay was a special treat. Thank you for all the time you spent researching and composing this piece and for your many contributions at the conference.

Do you use an app to track tastings and if so which one?

Kay, thank you so much for participating, and for your kind comments here.

I use Evernote to log my wine reviews. It syncs to all of my devices, so I always have my complete tasting database with me when I travel.

AWESOME on the Terri Gross mention; greatest interviewer alive. Whenever I lack for an interview question, I immediately all myself “what do I think Gross would ask here? ”

Perfect, Joe. Terry Gross pushes her subjects, kindly, somehow striking the perfect balance between curiosity and generosity.

I’ve blogged/written for over 15 years, but I’m new to the world of wine blogging/writing. Thank you for such an article…made me think about what I’m doing and why. It starts as a passion and builds from there. Btw, I never gave it a thought to use Evernote. Duh. Right at my fingertips.

So glad to be of service, Kat. And Evernote for wine reviews is great! Let me know how it goes.