Last week, wine writer Talia Baiocchi published the views of four industry professionals on whether wine labels should list the ingredients used in winemaking. Although she classified the story as a “Hot Topic,” her interview subjects—a sommelier, a winemaker, a distributor, and a retailer—seemed rather circumspect, withal. The consensus was that ingredient labeling is possibly helpful and sometimes confusing, and that engaged customers will find some way to get this information, anyway. The upshot of the article: Why bother?

My own views on this subject are likewise colored by my work in the industry as a wine marketer, wine writer, and wine educator. But my views are also colored by my status as a wine consumer, and I think the consumer’s voice is an important addition to the mix.

I’m an avid back-label reader. I like knowing what has—and by extrapolation what has not—gone into the food I’m about to eat. I favor foods produced with minimal intervention and least processing, foods that are in their purest possible state, and, to the extent possible, expressive of where they’re grown. I avoid foods that are genetically modified, hormone-fed, antibiotic treated, inhumanely farmed, or that contain artificial ingredients, preservatives, and additives. I’d rather go without a food—particularly meat and dairy products—than support industrial farming practices, which are often unethical and ecologically damaging.

I appreciate the existence of a national organic standard (albeit one whose creation was weakened by the interests of big business), and the federal nutrition and ingredient labeling requirements, because together these offer some assurance about a producer’s claims. Note that no one’s saying that you can’t make Cheetos. They’re only saying that if you do make Cheetos, you have to tell everyone what they’re made from, so people can decide whether to eat them. Personally, I don’t.

Wine is no exception. I don’t want to drink Mega Purple or citric acid (because I’m intolerant of it) or other additives if I don’t have to. So as a consumer: Yes. I would like to see more ingredient labeling on wine bottles.

Speaking as a marketer, though, I understand the complexities of this choice. First, I know that many consumers don’t share this level of interest in how their wine came to be. Some may care more that a wine taste the same from one vintage to the next, and so may be more willing to accept additives or other interventions in order to achieve such consistency. That’s not truly an argument against ingredient lists, though, because these folks could ignore the lists if they chose—assuming they actually understand what all that stuff is.

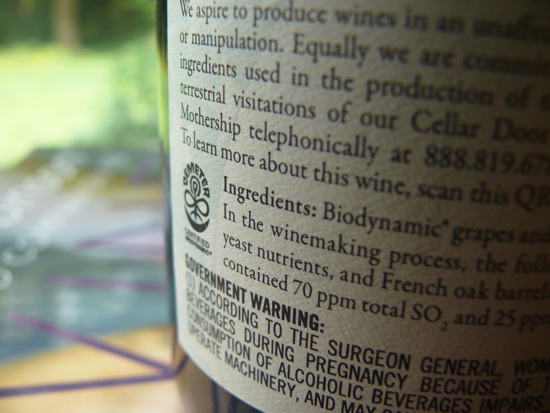

Relatedly, wine labels listing bentonite, isinglass, polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, and similar compounds do run risk of unnerving the public, or at least leading it somewhat astray. I saw this first hand when I worked in consumer sales at Bonny Doon Vineyard, a winery dedicated to ingredient and process disclosure. (The wine label pictured above is from their 2009 Syrah “Chequera,” farmed Biodynamically.)

On one occasion, we sent to media samples of a red whose label stated that untoasted oak chips were used in the winemaking process. In his review, a writer remarked that the wine tasted too oaky to him, and that he’d wished we’d skipped the oak chips. These, though, had been used only to stabilize the anthocyanin during fermentation; they were in contact with the must for a short time, and did not add to the flavor profile of the finished wine. Moreover, the wine hadn’t spent much time in barrel during élevage, so I wondered whether the reviewer had mis-ascribed the grippy tannins of a young wine to something he’d read on the label. In this case, the oak chips disclosure was a ruby-red herring.

But that simply points to the need for more and better education, plus open communication between winemakers, media, and customers. Transparency is an important corporate tenet no matter what the industry, and consumer goodwill eventually accrues to companies that commit to it, even if initially the terms are vexing and hard to learn. Education and media coverage has, for example, led to a public that now grasps the nutritional difference between a natural oil that’s solid at room temperature and a purposely hydrogenated oil that may contain undesirable trans fats. If engaged consumers can learn that distinction, they can certainly learn that bentonite is a harmless fining agent, most of which precipitates out of the wine anyway.

Which brings us to another argument about ingredient disclosure, viz., What, exactly, should be disclosed? Grapes for sure, but what about wild yeast, or cultivated yeast? What about nutrients, acid, sugar, sulfur dioxide? What about the dry ice packed around the grapes on that sultry harvest afternoon? What about those Bonny Doon oak chips?

The key, absent federal labeling requirements, is simply to use good judgment. Disclose whatever seems important according to your winemaking principles and to your customers. For example, while it may be true that many compounds are detectible in only trace amounts in the finished wine, I do believe most vegetarians and vegans would want to know if casein (from milk), isinglass (from fish), or albumin (from egg) were used in the winemaking process. These are all fairly common fining agents, yet many vegans are unaware that animal products are often used in winemaking. “Isn’t wine just grapes?” they ask. Well, no, it’s not. A sensitive producer will stay tuned to the information needs of their consumer, and disclose accordingly.

So speaking as both consumer and industry professional, I do believe that ultimately, disclosure will lead to a better-informed market, and that this could in turn lead to more consumers choosing wines that are less manipulated, with fewer additives. This would be a good thing. Granted, that’s my value system, not everyone’s, but given the alternative, I prefer to put my faith in the success of a thoughtfully crafted, non-mass-produced, and possibly more expressive wine.

Many thanks to Eric Asimov, wine critic at the New York Times, for recommending this article in the paper’s “What We’re Reading” column. Thanks also to Wine Business and Organic Wine Journal for recommending it to their readers.

Great article Meg, and an awesome topic! I attended a very interesting round table discussion on “label transparency” earlier this year at the RAW fair in London. The discussion was interesting, but somehow the conclusion was that it would be “too difficult right now”…

I also do believe that consumers would like a little more information than they are currently getting, and feel that winemakers such as Bonny Doon Vineyard are caving themselves a niche by catering to this desire for info or transparency…

I wrote up the RAW discussion for Palate Press a while ago and there were some interesting comments left on the post. Here is the link in case someone would like to check it out 🙂 http://palatepress.com/2012/06/wine/do-you-really-want-to-know-label-transparency-in-the-wine-industry/

Meg,

You mention that you are intolerant of citric acid and yet citric acid is (in small amounts) naturally occurring and in virtually all wines. So would listing “citric acid” on an accurate ingredient label dissuade you from buying the wine?

Adam Lee

Siduri Wines

Hi Adam,

Thanks so much for reading and for your thoughtful question. I’m aware that citric acid is naturally present in minuscule amounts in grapes. I’m more interested in whether a winemaker added citric acid to acidulate the juice, because this method is both inexpensive and often contributes an unwelcome flavor. It’s mostly used for very inexpensive wines, and is forbidden in the EU except for some rare use cases.

So, a disclosure about the addition of citric acid would provide me with two interesting points of information: first about the winemaker’s treatment of the wine, and second about the fact that, given enough of the stuff, I could end up uncomfortable. Would it dissuade me from buying it? Perhaps, but perhaps not. Knowing me, I’d probably try it at least once, just to check it out. But I would certainly appreciate having information that would let me make that informed choice.

Cheers,

Meg

Caroline,

Thank you for reading and especially for sharing the link to your Palate Press story.

I’m glad your article mentioned QR codes, as these do offer some promise. I introduced QR codes at Bonny Doon Vineyard to provide more information about vineyard sources, winemaking approach, aging windows, tasting and pairing notes, serving temperature, and the like. I agree that maintaining the QR landing pages is a hassle, but I think they could be worthwhile for the consumer both at point of sale and afterward, as he stands in his wine cellar scratching his head about what to open next.

Best,

Meg

Meg,

I think where my concern lies (and where we may differ) is in what is of benefit to the average consumer. Tell the average consumer that a wine with 9g/liter of tartaric acid (all of it natural) doesn’t need to list tartaric acid as an ingredient, but a wine with half as much tartaric acid (but a small amount added), needs to have it listed as an ingredient….and they will tell you that doesn’t make sense to them. Try it. I have, many times here at the winery.

Or tell the average consumer that a wine from Burgundy needs to list “sugar” as an ingredient but that the wine is dry, and they won’t get that either.

As wine geeks (which I proudly count myself as one of them) we care about these things, but consumers are concerned about what’s in the wine.

Adam Lee

Siduri Wines

Meg this discussion seems to go on and on with few, if any commenters apparently acknowledging that two completely different things are being discussed: ingredients, and process.

Ingredient labeling is Federally regulated, and generally is defined as what remains in the package in the consumer’s hand after the process is complete.

“Grapes” – don’t have to say organic, or biodynamically farmed, or any other description, just “grapes.” And If “grapes” are on the label there is no requirement to disclose anything that is naturally found in grapes, including all the acids, even if tartaric, malic or citric were added in the process, because there is no way to determine if the remaining acids were derived from the “grapes” or from the bag.

“Sugar” would be on the label if there is measurable residual, for example if Mega Purple was added before bottling. However there would be no requirement to disclose Mega Purple, because it is made from “grapes.”

If the wine is sterile-filtered there is no requirement to disclose “yeast” or “malolactic bacteria” however if the wine is not filtered and either yeast or bacterial cells are present, both would probably have to be disclosed regardless of whether they were “added” or not. And for “natural” wines? – they certainly have all sorts of yeast and bacteria in the finished product.

None of the fining agents: proteins, Bentonite, PVPP, etc. would be disclosed because they are – by definition – not present in the finished wine.

If (god forbid) we ever are required to do ingredient labeling I will be interested to see the final rule-making on barrels. Something like: “tannins, non-fermentable sugars, vanillin, syringaldehyde, and guiacols derived from French/American/Slovenian/Hungarian oak barrels.” Or chips, or staves, or powder. Corks, too.

If something like Quebracho tannin is added at the beginning of fermentation, will it have to be listed? It is virtually indistinguishable chemically from oak tannins, and very well may precipitate entirely from the wine, making it a processing agent.

The point I’m trying to make here is that the rule-making for ingredient labeling is complicated, and deeply technical. Consumers will not be involved in this rule-making.

Regarding process, “process” is intellectual property, and consumers have no right at all to have IP disclosed to them, on the label or anywhere else for that matter. That really should be the end of discussion on process. But I’m sure it won’t be.

Adam, if I read your comment correctly, we may indeed have a difference of opinion. You seem to lean toward less disclosure because the majority of customers either don’t care, or could become confused by it. I tend lean toward more disclosure, letting the consumer decide whether she cares or not.

I agree on more information is better than less. The people who do not care about ingredients are going to ignore this information anyway.

John, thank you so much for reading and for adding your voice to the mix.

On food packaging, ingredient labeling and nutrition labeling are quite different, and to some extent are designed to address the question about ingredients versus process. Ingredient labels list components used to produce the product, while nutrition labels show the resulting product make-up. For example, a sweetened yogurt might be made from milk, bacterial cultures, and honey. These three elements—whether the cultures are still live or not—will be listed under Ingredients, ordered by weight. Meanwhile, the Nutrition Facts will list the finished product’s calories, fat, protein, calcium, and similar nutritional elements, including total carbohydrate, which is contributed by both the milk sugar and the honey. Had the producer used corn sweetener to attain exactly the same finished sugar content, the ingredient list would change, while the nutritional info would not. (Note that no process steps need be revealed: the intellectual property of the yogurt manufacturer is preserved.)

I offer this example not to promote mandated nutritional labeling and ingredient lists on wine bottles, but simply to note the similarity to the situation in which grapes contribute some of the wine’s finished acids, while acidulation contributes others. Personally, I’d rather eat honey than corn sweetener, so enjoy seeing that detail on the yogurt label. I’d feel the same way about citric acid, too.

I’d also like to underscore the distinction between government mandated and voluntary ingredient and additive disclosure. Federally mandated disclosure would require the input of regulators, industry contributors, and consumer advocates. The process of obtaining consensus would likely be long and onerous, and industry would probably dislike the results despite their participation in the process, if only because regulation is anathema to industry. But mandated ingredient disclosure could also ultimately yield greater consistency across labels.

Meanwhile, voluntary disclosure requires only the thought processes of the producer and the input (if she’s smart) of her market. It’s less onerous, because producers can opt in or out at will. But this is not going to yield anything resembling consistency across labels. One winemaker will disclose a tartaric acid addition, and another will not. No one can rightly say whether this is good or bad, except us—when we have discussions like this one, or when we decide to buy the bottle, or not.

Right now I lean toward voluntary disclosure, and toward letting that test run for a while to see what happens.

I’m with Adam on this. And I’m not cynical about the intelligence of our customers but I’ve seen how transparency throws people off. We pack a lot of information on our back label and the first year I listed RS on a Gewurz bottle. It was damn near bone dry but because there was an RS number listed people shot me the familiar “I don’t drink sweet wine” even though there were red wines on the menu that had higher RS, while still being dry. I’d say it was dry, they’d taste, and say… “yeah. too sweet”

here’s the new version:

http://blog.cartographwines.com/2012/08/the-story-of-the-wine-on-every-label/

Alan Baker – Cartograph

Meg,

No, you are not reading me correctly. I am saying that consumers primarily care about what is in the bottle, but you apparently are less concerned with that….but about where it comes from. Wine geeks are more interested in process, consumers more interested in ingredients.

Adam Lee

Siduri Wines

Thanks, Adam, for clarifying. In fact I do care about both, and tried to be explicit in my article about my concern both for process and product. I regret if that wasn’t ringingly clear.

It wasn’t in the post….it was in your comment when you said, “I’m aware that citric acid is naturally present in minuscule amounts in grapes. I’m more interested in whether a winemaker added citric acid to acidulate the juice, because this method is both inexpensive and often contributes an unwelcome flavor.”

BTW, on the small producer end of things, I don’t know anybody that adds citric.

When you talk about food labels in response to John…where does something like velcorin in Gatorade fit in. It isn’t in nutrition information nor is it in ingredient listing (because it doesn’t exist as an ingredient after killing off the yeast cells).

Adam Lee

Siduri Wines

Alan, thank you for sharing your experience about the RS disclosure. I feel your pain. I’ve found that especially in pouring wines with floral aromatics—Moscato, Gewürz—many customers will sniff and wrinkle their noses, proclaiming their distaste for “sweet wines” even if the wines are bone dry.

Sometimes I can get them to taste it, and will try to help them access the difference between what they’re smelling and what their tongue is experiencing. In that particular case, it’s their nose that sets an expectation. In the case of a label RS disclosure, it’s their intellect (and their passion, evidently!) that sets an expectation.

But in any case, my guess is that if more wines were to list RS, wine customers could more readily come to understand that sugar on the tongue and sweetness on the nose are two different things. As long as we’re only disclosing RS on wines like Gewürz and Riesling, wines that are quite often sweet, we’re going to wind up with a public who associates RS disclosure with sweet wine only.

Adam, I am truly interested in both process and product. I’m not terribly interested in the minuscule amounts of a substance naturally occurring, but I’m quite interested in any quantity of that substance that’s been added.

The very nature of this commentary today is one reason I encourage discretion on the winemaker’s part about what’s worthy of disclosure. I’m not being willfully obtuse; I simply believe that as an industry we don’t have all the answers yet, nor even all the questions. And it’s why I think that for now, voluntary disclosure could help shake some of these issues out of the tree, so we can see clearly how best to move forward.

Meg,

I have to agree with John, I am an avid label/ingredient reader myself and most people would be amazed by how much sugar are in things for example, but wine is such a complex product it would be extremely hard to select which things should be listed. Most commercial wines are sterile filtered and when it comes to acid additions tartaric is mostly used specially in reds and to a way smaller extend citric, and if citric is added usually only very small amounts to “freshen up” the wine a bit.

Overall I think ingredients would confuse most consumers since they can not even really make sense of what wine was made from organic grapes or and if the wine was made under organic rules. Or even here in Oregon we have the “LIVE” program and some people use sustainable but most consumers have no clue what any of these terms actually mean, so bottom line for me the more info the more confusion.

Anyhow that’s my input here

Rene Eichmann

Winemaker Bridgeview Vineyards

Hi Rene, it’s nice to see you here! Thanks for reading, and for sharing your position. I do appreciate your desire not to addle consumers.

I’m not certain it would be wise to draw conclusions, but thus far in the comments the vote from winemakers has been a resounding Nay. This is why I believe it’s important to hear the consumer perspective, while acknowledging the complexities that labeling would visit upon industry folks. I do hope more consumers will weigh in here, not least to read your thoughts on the matter. Thanks again for participating.

Absolutely agree. During my pregnancies, my label reading and research into what I was putting into my body increased exponentially. I recently became aware of all of the additives that can be used in wine making and I was shocked. Now, that has not caused any change in consumption, but it does make me wonder.

I would love disclosure. Let me make an informed decision about what I am putting in my body. Even if there are additives in my favorite wines, I would likely still drink them in moderation. I, too, am all about food/cosmetics/cleaning products with the least processing/testing/chemicals. I try to consume with a conscience and am willing to pay more to do so. Teach us the purpose/origin of the additives and help us be conscientious in our drinking.

That being said, I would love for the winemakers to do this of their own choosing rather that create a govt. mandate that puts small producers in a bad position or requires inane labeling all over the pretty bottles. 🙂

Thanks so much, SAHMelier, for weighing in with your thoughts. I appreciate your moderate approach that asks first, What’s here? yet also provides latitude for producers to make choices about how best to answer that question for you.

I’ve thought about this a number of times, both because of my consumption of Bonny Doon wines and the content of their labels. Also because I make wine at home, do as little as possible, but still want to share what goes on with those who drink the wine and are interested in what had transpired.

Times are certainly trending towards the need for consumer access to info about the products they consume and acquire. At this stage, I see it becoming an important brand differentiating factor. It would be very interesting to see how that factor manifests across socio-economic lines.

The winemaking process is complicated subject matter for the label. We are talking about prime real estate, already some of which is aggressively occupied by the Surgeon General and ignored by virtually all who pass by it. If we even discuss the topic we should be equally interested in the ingredients of beer, cider, and spirits.

Let’s also consider if requirement for actual ingredient content would lead to increased overhead costs…and increased prices! Now you have the consumer’s attention. Is there any chance that labeling will give neo-prohibitionists surface area to work with, and frighten consumers?

Don’t get me wrong, I care about what goes into my wine, and try to choose as wisely as I can per my budget. Web based distribution of information by producers and importers is easily facilitated and increasingly expected than ever. While QPR pages may be a pain to maintain, they are potentially an authoritative source for information if the producer chooses to provide it. As a winemaker, and tasting geek, I already try to ferret out what I can about the process of wines I am interested in…it’s a necessary component of “Continuing Ed”.

It is going to be a voluntary process for the foreseeable future. If the FDA was in charge I could see it as a mandate, but the TTB mission is to collect taxes and there is no incentive to require it…if there is no ingredient listing on tobacco products there won’t be for alcohol either. Who knows what they put in guns and bullets?

It may be that the system will sort itself and those buyers that need information about the content and process will gravitate to the producers who give them what they want, both in and on the bottle. Others will stick to what works for them, and in many cases, less will mean more.

In vino veritas.

Caveat emptor.

The FDA’s requirements on food labeling are here http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/FoodLabelingNutrition/FoodLabelingGuide/ucm064880.htm

a quote:

“Should water be listed as an ingredient?

Answer: Water added in making a food is considered to be an ingredient. The added water must be identified in the list of ingredients and listed in its descending order of predominance by weight. If all water added during processing is subsequently removed by baking or some other means during processing, water need not be declared as an ingredient.”

As well the Canadian Food Inspection Agency defines them as ‘processing aids’ and does not require they be listed when there is no or negligible residuals remaining in the final product http://www.inspection.gc.ca/english/fssa/labeti/guide/ch2e.shtml

Here’s their list of processing aids exempt from labeling;

1. Hydrogen for hydrogenation purposes, currently exempt under B.01.008

2. Cleansers and sanitisers

3. Head space flushing gases and packaging gases

4. Contact freezing and cooling agents

5. Washing and peeling agents

6. Clarifying or filtering agents used in the processing of fruit juice, oil, vinegar, beer, wine and cider (The latter three categories of standardized alcoholic beverages are currently exempt from ingredient listing.)

7. Catalysts that are essential to the manufacturing process and without which, the final food product would not exist, e.g., nickel, copper, etc.

8. Ion exchange resins, membranes and molecular sieves that are involved in physical separation and that are not incorporated into the food

9. Desiccating agents or oxygen scavengers that are not incorporated into the food

10. Water treatment chemicals for steam production

Processing ingredients that are then later removed, such as fining agents, would not be required to be listed as they essentially do not exist in the finished product.

Fining agents, animal products or otherwise, would not be required to be listed. They’ve been removed from the finished wine. Vegetarians are left holding their breath hoping there are no residuals left behind. Or as little as they would personally deem acceptable.

Mega Purple is a grape concentrate so at best a label would have to say “grapes and grape concentrate”.

Wines with residual sugars would only need to list sugar as an ingredient if it was added to the wine. If no sugar was added and fermentation was stopped before all the natural grape sugars were turned to alcohol then sugar would not be an ingredient here, though the wine is sweet.

Yeasts would only need to be listed for wines left on the lees, like some sparklers. But those that have been disgorged may not need to list yeast as an ingredient, it’s been removed. Still wines that have been fined and filtered have had the yeast residues removed and in that case would have been a processing aid, not an ingredient. Quite possibly the same for malolactic bacteria. “Natural” wines don’t use added yeasts, just those naturally present on the grape skins, again no need to add yeast as an ingredient, it’s already a competent of the grape.

Yeast nutrients may be added but they in turn are consumed by the yeasts.

Other processing ingredients like calcium carbonate or potassium bicarbonate to reduce acidity, or potassium bitartrate (cream of tartar) to assist in cold stabilization, end up forming crystals that precipitate out of the wine later. Again, no need to list them, they are gone from the finished product.

I would even say that oak aging in a barrel is a process. The tannins and vanillins and esters, etc.. that get transferred into the wine from the oak would likely be exempt from ingredient lists. Their concentrations are very small, likely under required thresholds, and that list would get rather long as their are oodles of flavor components beyond the more well known ones being transferred during oak aging.

What you may end up with for an ingredient list for most wines is simply : grapes, sulfur dioxide as a preserving agent. That’s it.

Some cheaper and mass produced commodity wines might have an ingredient list of: grapes and grape concentrate, sugar, citric (or malic or tartaric) acid, sulfur dioxide as a preserving agent.

You probably won’t see much variation between those two sets of ingredient lists. At least in terms of what would be legally required to be listed.

Wine and alcoholic beverages are currently exempt from the rules that apply to most foods but if labeling became a requirement it’s very likely it would just have the same rules. To expect anything more from wine labeling would mean an entire re-write of the rules on all food labeling. If wine is exempt now how could you ever expect it to require more than other foods do now?

As to what was said about “process” and IP. Wineries would not need to disclose things like leaving the mash to sit for 8 days vs 10 days before fermentation. How often do they punch that mash down during fermentation? Or what strain of yeasts do they like to use? How much toast do they like on their barrels?

A winery could always choose to disclose all that in as much or as little detail as they like. Their website would be the place for that. As a wine geek I would not mind seeing a bit more detail than just “we selected our best grapes and aged the wine in French and American Oak barrels for 12 months”.

Perhaps there is a market niche for wines that specifically dont use any animal by-products as fining agents or stabilizing agents, and choose to highlight that fact in order to cater directly to the vegans and vegetarians? Or at least to those that care if there might still be some egg white in there at about 1 part per 10 million.

So really, the disclosure, how much or how little, is up the the winery. Until enough consumers demand otherwise, and then governments step in and force wine to follow the same guidelines as other foods you simply wont see detailed ingredient lists. If it becomes required some consumers may be disappointed in how little actually gets listed. Wineries need not fear ingredient lists, if they became required. The lists would be as basic, or more so, than many foods we already consume and customers will very quickly become accustomed to them. I even doubt many would steer away from their favorite cheap wines when they see grape concentrate listed.

Even Bonny Doon are being somewhat selective of their ‘disclosure’ and it comes largely from a marketing stance. They mention the process, and admittedly they do mention parts of the process that could un-nerve some customers (bentonite, copper sulfate) but also skirt things by saying ‘yeast nutrients’ which may actually be a mix of diammonium phosphate, dipotassium phosphate, magnesium sulfate, amino acids and other compounds.

Boony Doon labels have been this “transparent” since 2007-2008. Good on them. But has it impacted the market place? Have other wine makers felt the need to jump on the bandwagon else be left behind by consumers wanting transparency? The answer is no.

We wine geeks, wine bloggers, and other serious wine enthusiasts are a mere fraction of the wine consuming market. We may care more about these things. We may want to see the larger group of consumers be more informed. But frankly, we don’t matter. Labeling ingredient lists and process disclosures is, so far, a non-issue. But it certainly is great wine blog discussion fodder 🙂

WineCharlatan – Best explanation about wine additives I’ve ever read. Bravo! I’m on the wine production side, and I cringe thinking about full disclosure, simply because very few people understand what those ingredients even are, let alone how and why they are added. The worst would be the wine writers. The example given about the wine critic that thought there was too much oak, even though it had only seen oak during fermentation. But it was on the label. The other classic example are the people that see an RS number on the label, and thus convince themselves that the wine is sweet. It would become rampant. I hate to imagine what the sensationalists over at the Wine Speculator would do with full disclosure labels. They know less about wine additives than your average tasting room staff.

A very fun piece with good comments all around. I particularily liked the “oak chip” and “R.S.” comments. It’s very true. We label a lot of our wines “No added sulfites” (when there aren’t any added of course), there’s always one in the group that says “Oxydised”, they aren’t but that’s the connotation. It isn’t going to stop us from writing it on the label. I think the wine biz has been enjoying smoke and mirrors for a long time. I totaly get the average Joe coming home from a grueling day at work and saying “I just need a glass of wine, any wine”, but what’s wrong with letting them know what’s in it (or not). There will be questions, there will be confusion but eventualy there will be education and that’s good. The argument as to “What is an addition” is spurious and a red herring, if it isn’t the grape from the vineyard, it’s an addition. Keep at it Meg.

Todd, thanks for adding your remarks to the conversation. Label real estate is limited and precious, and as noted, QR codes hold some promise. So does good website architecture that lets a customer find wine information by starting at a winery home page; this is remarkably difficult on some sites.

Re. the TTB, in my experience they become somewhat flummoxed by ingredient disclosure on labels, and this adds drag to the approval process. That means only the most passionate producers will undertake to include it—or at least include it twice.

WineCharlatan, I appreciate your taking the time to develop a detailed commentary, which is so extensive it perhaps deserves its own comment thread.

To one of your points, and one also addressed by others: absent federal guidelines, winemakers are indeed on their own to determine what to include and exclude about their method, and what to say and how to say it. I think this is a good thing, at least in the near term, because I support a model in which a market determines for itself what it cares about, and only much later, if ever, a regulator steps in (preferably with a light hand) to ensure that collective good faith is maintained.

I don’t believe we’re ready to talk about regulation yet, but it seems evident the community has a good appetite for discussions like these, and is certainly ready for more experiments to flush out the issues in the market. And from a marketing perspective, it’s reasonable to assume that those producers who choose disclosure will seek feedback about the gesture. I certainly did at Bonny Doon. Perhaps another winery rep could offer his or her experiences here.

What’s most compelling to me about this commentary so far is the predominant opposition to ingredient disclosure from those on the production side. The primary concern cited is consumer confusion or apathy, but there’s also a strong vein of antipathy about the complexities of determining a reasonable standard. This is somewhat surprising, because complexity isn’t reason enough not to attempt something worthwhile. If that were true, the wine itself would never get made. Fortunately, for now, those who don’t want to disclose, don’t have to.

Phillip, thanks for stopping by and adding your views. I agree that after confusion comes education, if the communicators (and I’m one) are doing their jobs.

Meg! Another brilliantly written article and a most worthy topic. I can only say that I agree with you 100%!

Meg ~ Brilliant post and the responses are stunningly Humbling in their scope and depth.

My immediate reaction was to wince at the thought of Government Intervention into the hallowed grounds of vineology. My cynical side has long thought that with the explosion of growth in the US wine industry, the Government is not long to be satiated with mere tax income and this may be just the introduction of the regulatory entry point they long for. The licensing, fees and such which feeds another layer of bureaucracy seems eminent, as greedy politicians attempt to “Get in on the action”. Let’s hope this discussion doesn’t ring the dinner bell!

Cheers La Mia Bella Amica

I love this statement:

“I’d say it was dry, they’d taste, and say… “yeah. too sweet””

Clearly the customer did not taste trehalose, sucrose, arabinose or any other non-“reducing” sugar in the wine and say that it was sweet.

Obviously the taster was a novice, and a rube for not convincing himself that there are only 2 possible sugars in the wine.

Buy a cheap HPLC and a cheap RI detector and learn how much and which sugars are in a wine before you automatically assume the customer is wrong. The customer was probably right, to be quite honest.

Every winemaker seems to act as if they know what is in their wine, but they don’t. 95% of the wine is a mystery because simple, long-term analysis is not done. I know it’s more important to decide what works better between a punch-down or pump-over, and how many times to do that a day, rather than get trained in analytical chemistry. Of course that’s why we end up drinking so much plonk these days…

“Isotope” it happens that I and a number of my colleagues actually ARE trained in analytical chemistry. I can tell you that “plonk” is exactly what you get when you start believing that chemical analysis should drive wine “improvement.” That said, I’m not sure how your comment bears on the question of whether or not wine producers should disclose ingredients and process, either voluntarily or otherwise.

Well “John” if you think that poor wine is made by “Terroir” or using “Biodynamic voo-doo” then I’m sure reason is outside of your realm of understanding.

The customer base knows far more than you think they do, and you should put on your label “If you are a customer that thinks this white is sweet, you are a moron, cause I tested 2 of 20 possible sugars in my wine, and since those are the usual ones, you are an idiot.

Wine is a product of fermentation. This is a scientific process, which those with Microbiology degrees seem to understand, far more than those without.

The label should read

“X g/L biogenic amines”

“X g/L Copper” (I’ve seen “wine-maker” maths before)

“X g/L ETOH by GC”

“X g/L Y sugar Z sugar B sugar by LC-RI”

“X mg/L Free SO2

product contains egg or milk or peanuts etc.

Beyond those above, I think that would cover the main customer concerns.

Ever since voo-doo, uncleanable concrete eggs, and team-preparation-deer-bladder-chamomile became the main concern of the average lemming wine-maker, quality has fallen into the toilet. Just do another 15 day “cold soak” so that those bacteria can make up enough waste to make the wine taste like a truck stop toilet. Brilliant.

John and Isotope, I do enjoy a healthy debate, although this one reads somewhat more like dispute. (But caveat lector; this is a blog comment stream, after all.)

I think what I’m hearing you both say is this: customers are capable of being both knowledgeable and skeptical; winemakers, meanwhile, need to be knowledgeable and ready with answers when questions arise.

I expect winemaking and enological details are most welcome when they’re stated plainly and in a way that respects the customer’s intelligence. It’s usually a good strategy to give the customer benefit of the doubt regarding his ability to assimilate information; in other words, to assume limitless intelligence but limited prior knowledge.

If a winemaker believes in his production methods, he’s at liberty to explain these, letting the customer decide what to do with the information. Isotope would likely want to know if, for example, a winemaker followed biodynamic principles, since the practice seems to provoke in him considerable animus.

So caveat emptor—but it sure helps the emptor if the producer tries to meet him at least partway.

Nicely done.

There is no easy answer here. You articulate that well.

The issue of course is that there is little to no information today about most wines either on the bottle or from the vineyard.

With that any information will be glaringly obvious and raise questions. That is goodness in my opinion.

The consumer asking the retailer what all this means opens the conversation and brings the consumer into the know. Those interested enough to read the label, will ask IMO.

My suggestion, labels aside is that every winemaker should take control of this and provide the real facts and details on their sites so there is a source. And not having a true source of the information somewhere is a larger problem.

As an example of someone that does this well is the tiny winemaker that I write often about, Domaine de la Tournelle in the Jura.

Sure they are pretty natural and don’t add much but search any wine on their site and they tell you everything anyone would ask.

They also of course, make amazing wines.

Arnold, many thanks for taking the time to read the article and add your thoughtful remarks.

I agree it would be a great benefit to consumers for producers to include process and ingredient details on their websites—and also ensure this information is readily findable.

Cheers,

Meg

Great article and comment stream. I’ve been suffering from this dilemma of what to list on my labels for a long time now, and at last this year I’ve decided I’ve had enough of analyzing and weighing up the pros and cons, etc and so I’m just going to everything I feel like listing and take the consequences, if there are any, and devil take the hindmost or whatever! I’ve always been in favour of transparancy and of providing as much info as possisble so that consumers can make an informed choice of whether to purchase or not. But maybe too much info is counter-productive. I dont know. Like I said, I’m going to list everything I can (ingredients and processes) and see what the feedback is 🙂 The decision was a load off my mind 🙂

Thank you, Fabio, for adding your voice here. I support your approach and admire your willingness to disclose what you think is most critical, then gird yourself for the consequences—good and bad. I’ll look forward to hearing how your customers respond. Onward!

Colleagues, an update: Eric Asimov, wine critic of the New York Times, read this article back in August, and kindly included it in his “What We’re Reading” dispatch on 8/20/12 (see http://dinersjournal.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/20/what-were-reading-504/). He also told me then via Twitter that having thought about this issue a bit more, he favors full disclosure of both ingredients and processes on wine labels.

Eric has just published an article in the Times reflecting this sentiment and echoing many points in this article. You can find his new story here: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/10/dining/bonny-doon-vineyards-labeling-policy-draws-little-attention.html?pagewanted=all

Very rare to see wine ingredients in the label. I had wanted for corporate catering services to have organic red wine. I’ll seek out that wine.

Hi Meg,

I am coming from the consumer side and felt invited by your comments to post.

I came across your article while I was researching toxins, allergens, and additives, for a friend who is having some big reactions after consuming beer. My husband and our close family are in town and enjoying a lot of wine over the holidays too. (Wine is the main thing that brings our family together from cultures as varied as Scottish, Peruvian, Filipino, and American, so I have some emotional investment in supporting our wine-drinking as long as they are all healthy!) They all have their own health quirks that I am watchful for, especially those in my parents’ generation. So this topic is close to my heart. I myself do not drink wine.

I very much appreciated reading your article and hearing all the viewpoints. I can empathize with those who are concerned about confusing customers, and I as a consumer of healthcare can absolutely validate this. In regards to healthcare, there is so much medical information out there, and so many biases as to what is healthy and not, it really is confusing. In my view, (staying with the healthcare example a little longer), there is a real lack of pure information with no bias, or at least aware, conscious bias, for a consumer to learn from. A place to start, a voice to trust. (I realize that this is a different topic but I see some similarities.) So I can appreciate it when those in marketing are truly interested in open discourse with the public, welcoming potentially uncomfortable questions, instead of taking a defensive stance. I can appreciate that this would be hard to do because of the relative ignorance of the consumer, and honestly we don’t know what we will learn about what is helpful and harmful for the human body. And to top it off, this varies from person to person. And yet it’s exactly because of this that I see a real opportunity for marketers to fill this huge need, and become empowering, trusted teachers/interpreters. Personally, I don’t expect a wine maker to tell me that the wine will improve my health or reassure me that it will have no negative effects on me. An honest conversation with a sense of humanity on both sides, is all I can ask for as a consumer. Even if it means saying, “I would like to tell you more but I am worried it will cause you unnecessary worry when I truly believe, based on the experience I have, that it will be fine.” I realize with the risk of lawsuits and liabilities that this kind of vulnerability may be unrealistic in our culture but it is my value, and I would absolutely respond to a maker that strives for this as well.

Thank you for having this conversation, and for facilitating it so respectfully.

Patty in the Bay Area, California

Hi Patty,

Thank you so much for reading, and for adding your voice to the commentary. I appreciate your nuanced view of this complex issue, and like you, hope more wine marketers will decide to embrace transparency in the spirit of, as you so aptly put it, “honest conversation with a sense of humanity.”

Cheers,

Meg

Have you seen the Gambero Rosso letter that Jeremy Parzen just translated? I recommend the read.

http://dobianchi.com/2013/02/18/natural-wine-gambero-rosso/

I directed them to this piece in the comments.

Thanks, Alissa. I had seen the story, and greatly appreciate the cross-reference in its comments.