Welcome, we’re glad you’re here. Please step inside the vestibule. Stay on this side of the barrier, for now, while we explain.

When you visit the Cellars at Jasper Hill, you must shed your outer self. First remove your boots, tiptoeing around the slack snow pooling at your socks. Stow your backpack wherever there’s room. Remove your parka and hat, scarf and gloves. Then your watch and all of your jewelry. Put it someplace safe, because it is not safe for the cheese.

Now, step over the short threshold that separates Out There from In Here and step into whichever pair of loaner rubber boots fits best. Snap on a Tyvek lab coat, and crown yourself with a hair net. Advance through a shallow tray of sanitizer to purify your shoes — yes, the shoes they have just loaned you — and proceed to the sink to wash your hands with antimicrobial soap. Thereafter, touch nothing, especially not the cheese.

I was allowed my camera, but my notebook and pen would have to be sterilized. This sounded ominous. And anyway, with no pockets and no backpack, how was I to juggle all of the tools of my craft: notebook, camera, recorder? Regretfully, I ditched everything but the camera, choosing to relying on a mix of memory and the mathematics of imagery, each picture worth a thousand words.

The Cellars at Jasper Hill are not open to the public, for reasons that should, by now, be obvious. But last month I had a rare opportunity to tour the caves in Greensboro, Vermont, where the company ages its own cheeses and provides affinage and sales support for local creameries that lack the expertise, the space, or both.

My host, Mateo Kehler (above), co-founded Jasper Hill Farm with his brother, Andy Kehler, in 1999. By 2003, their small herd of Ayrshire cows was beginning to crank out cheese, and their project soon caught notice of Cabot Creamery, one of Vermont’s oldest farm cooperatives. Would the Kehlers be interested in aging Cabot’s new experiment, a small-batch cheddar made solely with milk from nearby Kempton Farm?

The results were superlative: Cabot Clothbound Cheddar won Best in Show at the 2006 American Cheese Society competition. The success prompted the brothers to expand their affinage program, and along with it, their physical plant. They blasted open the stony hillside and built seven concrete vaults, each dedicated to aging a different style of cheese. Then they plowed the earth back on top. At 22,000 square feet undergroud, the Cellars at Jasper Hill is one of the largest cheese aging facilities in the U.S.

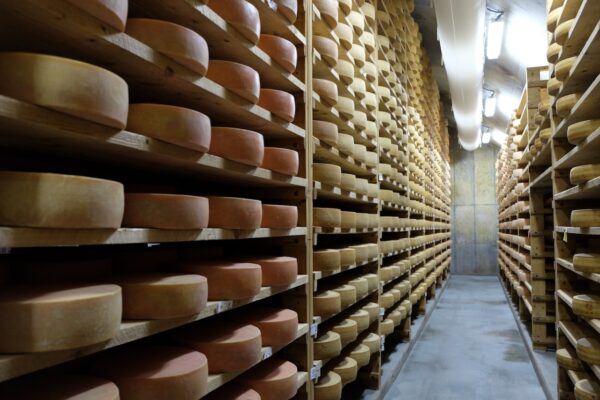

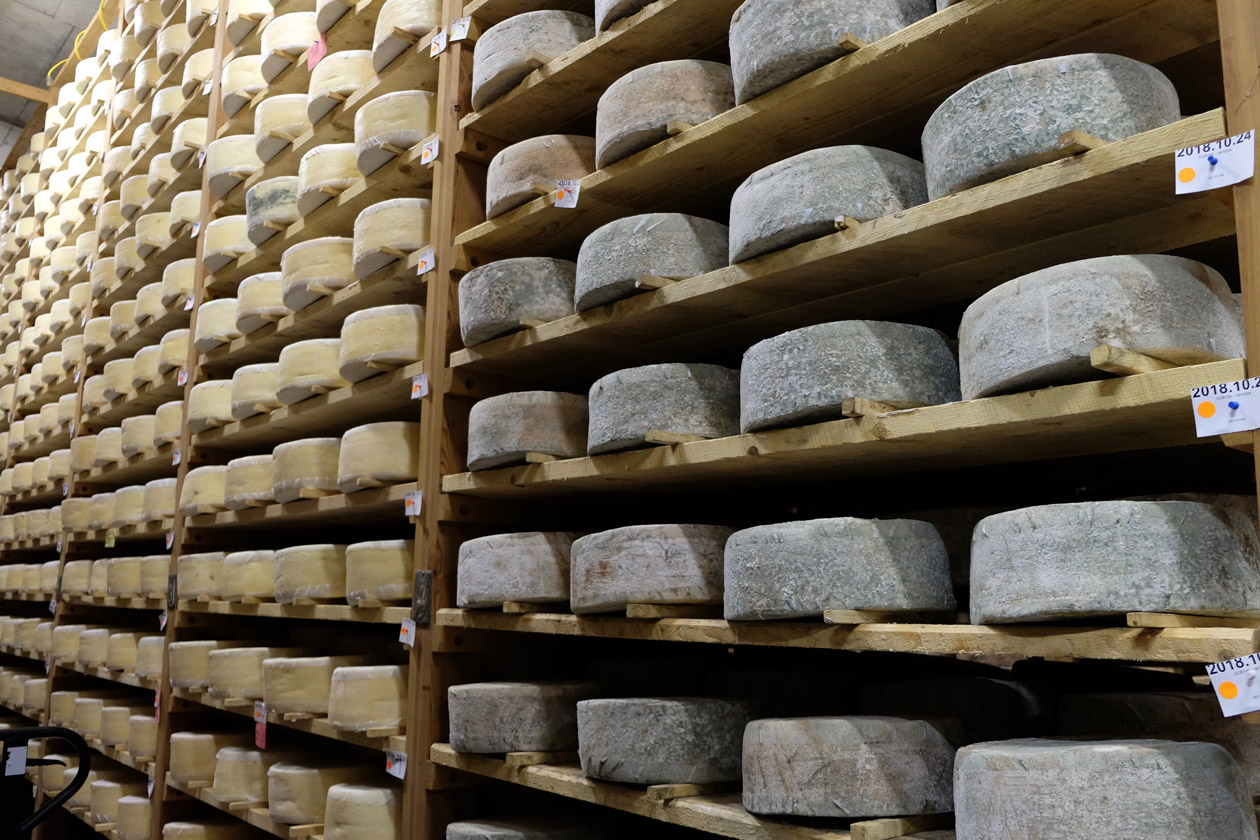

Kehler is an animated guide, knowledgeable and profoundly engaged with his craft. He speaks in complete paragraphs while making theatrical gestures with his hands; he might have been a Shakespearean actor had he not found his way to milk. The tour began in the one of the larger vaults built specifically for cheddar affinage. The room was radiant with the mushroomy, brothy aromas of aging wheels. As we progressed vault by vault, each one exuded a unique and distinct fragrance: pungent for the blues, mild and milky for the bloomies, nutty and savory for the Alp-style wheels.

This difference is essential, even existential, said Kehler. The crew strives to develop, nurture, and safeguard the microbial cultures in each room. The humidity, the temperature, the quality of light — all of these are important, but the dynamic interplay of bacteria and molds in cave and cheese is critical to fostering the perfect evolution of each style of wheel. The cellar affects the cheese, the cheese affects the cellar. The aging process, in other words, is a dialogue between place and milk. The cave is an element of terroir.

The cave is also a bank vault. Cheese, like wine, is seasonal in both its production and its consumption. People ramp up their cheese-eating during the fall and winter holidays, but demand drops precipitously in January. The smaller, softer cheeses, which take only a month or two to ripen, are ready for market during that peak season, netting the cheesemakers a prompt return on their summer investment. It’s a way to move milk fast and early, said Kehler, without incurring aging expense.

The larger, harder cheeses, which cellar for 8 to 14 months, come to market later. They can be released more slowly because they are not as fresh and fragile, thereby smoothing the economics for the affineur. As they sit upon the shelves, they gain value while compounding savoriness; a single 32-pound wheel of Cabot Clothbound Cheddar retails for nearly $1,000. These cheeses are a way to store capital, said Kehler. Solid gold, like bullion.

What’s next? I asked him. The milk, said Kehler. Meaning, first, the hay, because wet hay is anathema to raw milk cheese. New England’s moist, temperate summers conspire against hay drying, and bales are often put up with a high moisture content. Microbes get to work inside, and these unwanted organisms find their way into the cow and her milk. This isn’t a big deal if the cheesemaker is pasteurizing the milk, but with raw-milk cheeses, the milk’s microbial complexion is paramount.

Kehler’s goal is to get good microbes into the milk early, he said, and that means dry hay. For inspiration, the team looked to Emilia-Romagna, specifically to the cheesemakers of Parmigiano-Reggiano, who use specially fabricated hay dryers to ensure clean results. Using the same German manufacturer that has built facilities for the Italians, Jasper Hill constructed the United States’ first dedicated hay-drying barn. Powered by an 11,000-square-foot solar array, its blowers can get a rolled bale dry in six hours versus the many days it takes under New England’s fickle sun. Flash-dried hay also retains its nutrients and flavor, reducing the cow’s dependence on supplemental grain.

All of this work is admirable, but the results must be delicious. They are. Find my previous notes on two cheeses from Jasper Hill Farm’s own herd, Harbison and Bayley Hazen, plus three they age for others, Weybridge, Landaff, and Kinsman Ridge. If you’re ready for a taste, the company has graciously offered readers a 15% discount for first-time orders in their online shop. Use the coupon code HOABPMO at checkout (no, I don’t get a cut).

I took over 100 photos inside the Cellars at Jasper Hill, and below are some of my favorites. What did I see, mostly? Deep expertise, fanatical attention to detail, commitment to continuous improvements, generosity toward fellow dairies, a nuanced understanding of terroir, and the passion to work hard for great cheese.

PHOTOS

Coda: Isn’t it interesting that the affineur removes his jewelry, while the physician keeps his on?

I’m grateful to hosts Mateo Kehler and Zoe Brickley of Jasper Hill Farm, and Eleanor Léger and Jennifer O’Flanagan of Eden Specialty Ciders, for the opportunity to visit the Cellars at Jasper Hill. I regret that I was unable to quote Mateo Kehler directly. But, you know — notebook.

Glad that you get a chance to visit the inside cellars at Jasper hill. This is so cool!

Thanks! Yes, it was a nice surprise to be allowed inside the aging caves and to be permitted to share these pictures with readers.

Wow, finally got around to reading this and so glad I did. Love the diligence, focus on craft, and the integration of new technology. So interesting, and makes me want to try their cheese!

Thanks for reading, Bruce. Jasper Hill’s cheeses are definitely worth chasing down.