Camp was a motionless place, a place out of time, seemingly unchanging year after year. The big rock was always the big rock, the sunfish adoze on her nest, the bull pines towering, the children’s drawings pinned to the pine wall, the trophy fish framed taxidermically. The smell of old wood and damp woods.

But we changed, I changed. The first year it was all of us. The last year it was just three: Mom, Dad, me. One brother was working. One brother was having girlfriend problems. He talked about this with Mom, both lying near me on a blanket on the camp lawn, me unseen. I heard him say, “I love her, but…”

That night on the little black and white camp TV with a rabbit-ear antenna we saw a horror movie with vampires, stupid and scary, and afterward I lay alone in my hot upstairs bedroom afraid to move, terrified, then terrified for days, with a nauseated feeling in my stomach, trying to rid myself of the terror and of the idea of my brother in love.

But mostly by then my preoccupation was boys. And that was the last year.

There were a lot of sweet foods in our house, always. Mom baked often — cakes and brownies and pies and cookies. I was a skinny child and the effects of the sugar and fat never stuck. The habit of sweets felt pure and natural. For Mom it was I love you. Eat: I love you.

She made pies and cinnamon roll, brownies, blondies, chocolate chip cookies, banana bread, pumpkin bread, chocolate cake, angel food cake, yellow cake with white frosting, sheet cakes and sticky buns and scones and muffins. At Christmastime the baking reached a fever pitch, with sugar cookies for decorating, fruitcakes for neighbors, savory spiced pork pies we French-Canadian Americans called tourtière, and Lebküchen and Pfeffernusse, which she’d learned to bake when she and Dad were stationed at the Air Force base in Germany in the early 1960s, when he was listening over the Eastern Bloc, imagining himself a spy.

Mom made Whoopie Pies once, an extravaganza. The enterprise spread across the kitchen, its table, the counters. I helped with my small fingers. My mouth.

Nowadays Whoopie Pies are fashionable, but forty years ago they were a rural Northeastern phenomenon, possibly even a strictly Maine phenomenon. A Whoopie Pie is two little cocoa-chocolate cakes with a sandwich layer of white filling. Many cheat on this filling, using a greasy blend of shortening and sugar. But the proper Whoopie Pie has a starchy, milky pudding filling that’s whipped with sugar to form a fluffy center more creamy than oleaginous. The cake part is made by dropping batter onto sheet pans and baking it into shiny brown mounds. These are springy and dry at first, but as they age they absorb moisture from the air, making their surface clingy and sticky, so that the act of eating a Pie becomes an act of alternately biting the cake and licking gooey cake from the fingers.

There is a natural and correct way to eat a Whoopie Pie: First, lick around the perimeter to clean the edge of filling. Then take a bite, careful not to bite down too hard so the filling won’t goosh out. Bite, lick, bite, lick, repeat; cocoa-y chocolate creamy sticky perfection. At last, lick fingers clean.

The cake, that sweetness, obliterated care.

Each year for a few years we took a family vacation, sometimes for one week, sometimes for two. It was our only family travel apart from daytrips to the beach (fresh or salt) and exquisitely rare pilgrimages to local sites of interest, trips so uncommon that I remember few and little of them. Our vacation getaway was only a fifteen-minute drive from our home, a housekeeping cottage under the pines, one of about a dozen camps on a peninsula of a freshwater lake in Central Maine. Maine is puddled with lakes and bogs, so we could have stayed at any number of rental cottages near our house. But my parents happened upon this particular clutch of buildings on Salmon Lake in Belgrade, and we rented the same cottage several years running, from the time I was about nine until I was an early teenager. My mother had grown up going to a private camp in Belgrade when she was a girl, a one-room building her family owned, because it was not uncommon then for people even of modest means to have a little place on a lake, because there are so many lakes in Maine, and because there were so many fewer people then.

The cottage we rented in the 1970s was rustic; raw pine walls, browned with age, its rooms peopled with creaky furniture. But it had a full-width screened porch from which the adults could see us swimming and hear us if we became in extremis. There was electricity, and running water, but only cold water, and a real flush toilet. No hot water, no hot showers, so bathing happened in the lake, with a bar of Dial soap and a bottle of bug-juice-green Clairol Herbal Essence shampoo. You’d emerge smelling of freshwater fish and the stewy, tannic tang of a freshwater lake in the woods, plus a pungent overlay of scent that was some chemist’s idea of what nature smelled like.

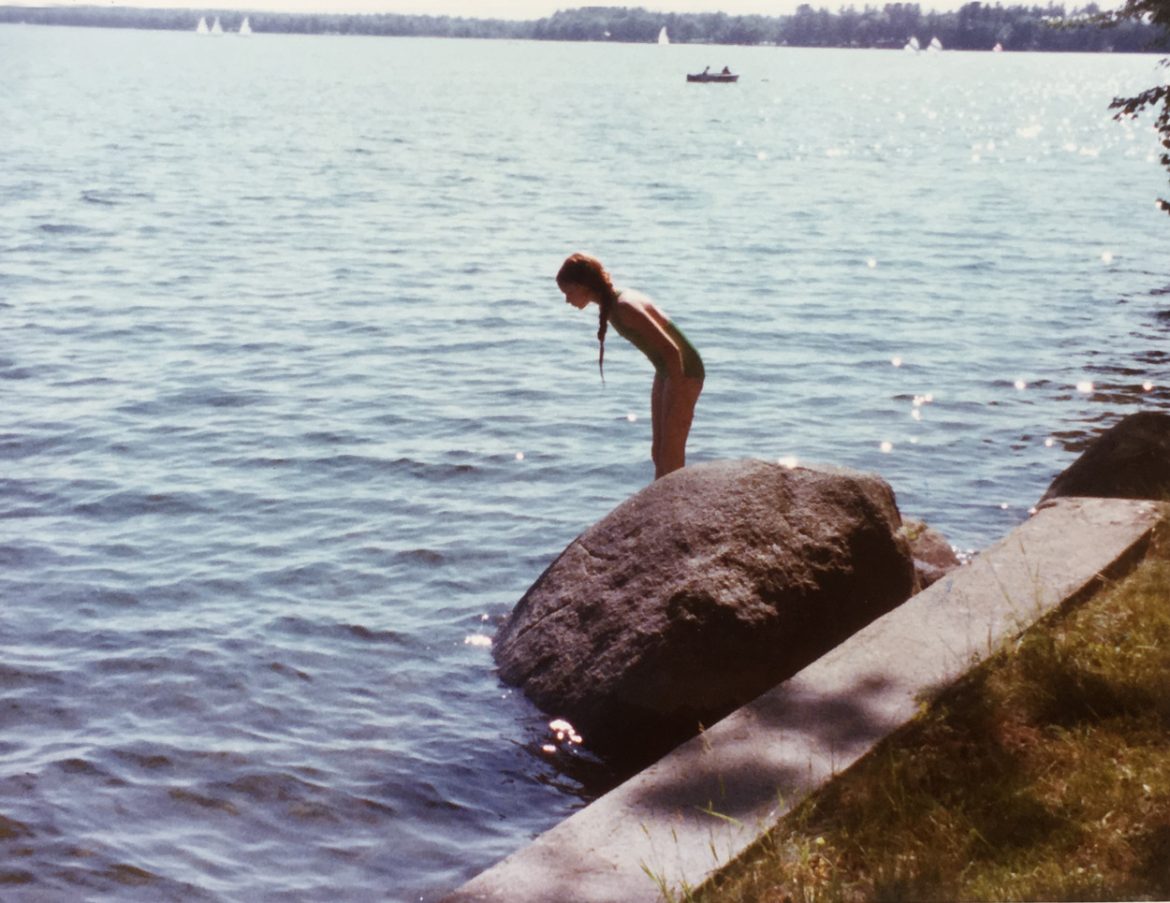

The days at the cottage were nearly indistinguishable, one following from the next in sonorous sequence. Still mornings the lake was a glassy sheet, with the shush-slip of a canoe paddle from an early riser before the day opened high and fine as if riding a thermal of whirring of crickets. I would pull my kelly green one-piece bathing suit onto my body, a body that had not yet started changing, my legs two thin white poles under a taut, smooth torso, and snap the straps one then the next over my shoulders. And taking a fishing pole, I would bait the hook with bacon fat and walk to the big rock at the corner of our camp’s lawn (no beach) and dangle the bacon for a sunfish, who would drowsily circle it before returning to her nest of eggs lying in a moon-crater of stones and sand in the yellow shallows. After I tired of this I would wade out alone and swim a little, just a little, because I was a poor swimmer, my lean, lanky body not at all buoyant, my legs too heavy for me to hold aloft, floating. My brothers were strong swimmers, and later in the day, when the heat was up, they would take laps between the dock and the shared float, and once on the float they would horse around taking turns throwing each other in, shouting in time-delay.

After, I would peel the suit from my body, wrap my wet torso in a thin towel, and pin the suit to the single line of rope swung between the sticky pine trees, gingerly stepping among needles and pine roots with my tender feet, so unaccustomed. Then a little later, lunch, on the lawn or porch, and the obligatory thirty-minute wait for lunch to “settle” before returning to the water, so I would not get a cramp and drown. This is a myth perpetuated by my mother, who likely learned it from her mother, at another camp on another lake nearby, different but the same, so long ago, and everywhere.

The afternoon, later, was lit by languid heat and the soundscape of lapping water, the call of crow or harrier, shouts from the distant boys’ camp twisting into dissonance in the thermal cells above the water. Much later, in the purpled night: loons.

We returned to this camp each summer until I was about thirteen. At that point my brothers, five and six years older, were away at their summer jobs and tilted toward adulthood. I was alone inside my changing body, wondering what would come next, longing for a boy to flirt with. The camp loop I walked the first year as a child, simply to walk with my mother and my dog in the evening, after the supper had cooled, had become the camp loop I walked alone at high day wearing sticky, fruit-smelling Bonnie Bell lip gloss and my first bra, hoping to meet a boy. But there were no boys, that last summer or anytime. Just the ones away at the boy’s camp across the lake, unseen and unseeing. There was no object of desire but desire itself.

Mom gamely cooked through our meals in the unfamiliar camp kitchen that over the years became a little more familiar, using the one tap in the huge tin sink that spewed cold well water, clanging the aluminum pots dented with the unfelt care of hundreds on the big gas stove so different from her customary electric, but so familiar from others early in her own life.

The rules were different at camp, so we had junk food. We thought it was special for us, but in hindsight it was special for Mom: easy, no baking, no production. She bought cookies and other sweets, Twinkies and Ring-Dings, and those Suzy-Qs, which I remember best. A Suzy-Q is a Whoopie Pie’s junk food pseudo-doppelgänger, two crumbly oblong chocolate cakes sandwiching a greasy white filling. I would not find it delicious now, but it was fiercely delicious to me then; rare, plus individually wrapped.

I have a memory, very precise, from the last year of camp. I’m tall now, reaching down a box of Suzy-Qs from the single pine cupboard in the kitchen, feeling a rush of anticipation of the forbidden-not-forbidden. I am tearing open the thin cellophane membrane and exposing the little brown cake, and then I am carrying it to the screened porch to eat, standing. I am alone with this cake, all desire. I lick it first around its equator, then I take a bite, careful not to smoosh it too much, then lick again, as the wake of a passing motor boat laps the dock, the motor smell drifting through the screen and wooden slats and mingling with the wet stone smell of the lake’s warm margin and the chocolate smell of cake and sweet white grease, and I’m biting it and licking again, and so fast it’s gone and over, and I’m licking the sticky crumbs from my fingers.

Nothing after that.

Food memories are so powerful. Connecting food and place makes intuitive sense regardless of whether the food has an actual connection to the place. Your story evokes food and drink memories for me that are tied to a particular place. Chcocolate cake and cream cheese frosting will forever live in Somers, CT, no matter where I ate it. Sweet iced tea is tied to my memories of East Harwich, MA. Fried chicken will forever live in Ludlow, VT. Choclate chip cookies will permanently travel with my mother, wherever she resides.

Nice memories.

Thank you for sharing those memories, David.

Absolutely lovely. Thank you for taking us into a moment of your youth as you share your journey of Suzi Q’s from youth into adolescence. Reading this took me back to summers at my grandma’s house (Mimi) in a small town south of Atlanta. Life there was slow and revolved around food – homemade biscuits, sour cream and caramel pound cakes, fresh peaches with sweetened condensed milk before bed, “coffee” comprised of mostly milk and sugar in the morning, southern style green beans that I called “grandmother beans” baked in lard with all its deliciousness. Staying with my Mimi brings up many cherished memories, each one inevitably involving food. She will be 100 years old in December.

Meg,

You are an uncommonly elegant writer. Enjoyed this tremendously; reminded me of how much I loved reading the (pre-Tina) New Yorker many years ago. Will spare you the deets of my food memories, which are tinged with violence: from cracking open steamed crabs with a knife and hammer in the sweaty confines of Baltimore crabhouses to standing back-to-back with Karin at Mardi Gras in Mobile, AL, circa 1989, trying to avoid being clobbered by a crowd clamoring for Moon Pies being tossed from parade floats. We each managed to score one, and they were good (tho’ not as good as Whoopies).

Moon v. Whoopie http://www.erinnudi.com/2018/01/10/difference-moon-pies-whoopie-pies/

Jamie, many thanks for reading and your kind words.

Thanks also for the amuse bouche of your own food memories; now I want the meal.