Rekindling Community

In 1985, third-generation stone mason Dale Hisler built a wood-fired bread oven on town land in Norwich, Vermont, just across the river from Terroir Review HQ. In the decades since, community members have used the site for gatherings large and small, pulling countless loaves of bread, wheels of pizza, and other forms of carbohydrate from the dome of wattle and daub. Last summer, with cracks threatening the oven’s demise, a crew from nearby King Arthur Flour, led by wood-fired oven expert Richard Miscovich, rebuilt it. Videographer Evan Kay captured the process in a short film.

“King Arthur thought it would really reinforce the mission of strengthening the community through baking, not only in building the oven but in getting to know each other, and knowing that we’re providing something for the future community.”

Watch: Building an Outdoor Clay Wood-Fire Pizza Oven

Reclaimed Redwood

In December 2021, the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council re-possessed a 523-acre coastal redwood forest in Mendocino County which was originally indigenous hunting and fishing grounds. The old-growth tract provides habitat for endangered species, including the spotted owl, and serves as a watershed for coho salmon and steelhead trout. It will again be called Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ, (tsih-ih-LEY-duhn) meaning “Fish Run Place” in the Sinkyone language. The transfer was facilitated by the conservation organization Save the Redwoods League.

“Renaming the property Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ lets people know that it’s a sacred place; it’s a place for our Native people,” said Crista Ray, who is of Eastern Pomo, Sinkyone, Cahto, Wailaki and other ancestries… “It lets them know that there was a language and that there was a people who lived there long before now.”

Food Webs

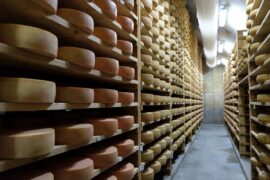

Food insecurity has been one of the pandemic’s most vicious side effects, as economic stresses have forced many households to scrape by with less, or less nutritious, food. In Vermont, municipalities and nonprofits have been devising novel solutions to the problem, in part by linking production and distribution to build a complex and mutually beneficial web of support. Whereas previous success was measured in the weight of food handed out (think: three-pound blocks of cheddar), these new strategies are proving to address multiple bottom lines. Melissa Pasanen filed a comprehensive — and incredibly encouraging — report in Seven Days.

“The crisis also opened a door to a long-overdue reinvention of the charitable food system in Vermont. It brought opportunities for government, private businesses and nonprofits to collaborate on new ways to deliver food, to reduce barriers to receiving food assistance, and to connect restaurants and farms with those in need. ‘We were forced to rethink how we do our work,’ said Rob Meehan, director of the Burlington nonprofit Feeding Chittenden. ‘The pandemic taught us you can do it different.’”

Read: How Pandemic Need, Federal Dollars and Local Collaboration Are Driving Better Ways to Help Food-Insecure Vermonters

Sugar Coated

In the food newsletter Vittles, Lily Kelting, Ph.D., invites us to consider the legacy of colonialism and the role the cacao farmers play in the origin story of so-called craft chocolate. The narrative promise of bean-to-bar chocolate lies in the linkage between origin and expression, but the purveyors’ storylines frequently elide nuances about terroir and farming expertise and erase the harsher realities of production.

“… the ultimate flavour of the chocolate bar, the cultural component of that terroir you’re tasting, is controlled by farmers in the Global South, not chocolate makers in the Global North. Working with beans, the very origin of chocolate, is fundamental for bean-to-bar chocolate makers; it is why many contemporary brands list their beans’ sources in big type. But in the descriptions of their chocolate, European and American chocolate makers choose to give more credit to themselves for sourcing quality beans than to their farmers for growing them.”

Read: The Perils and Promise of Bean to Bar Chocolate

Good Goods

Winners were just announced in the 2022 Good Food Awards, which celebrate delicious, small-batch products made by producers who meet high standards for social and environmental responsibility. This year the nearly 200 winners hail from 39 states and fall into categories like charcuterie, cheese, chocolate, cider, coffee, confections — and those are just the Cs. (Curiously, although there are awards for beer, cider, spirits, soft drinks, and other elixirs, the list does not include wine. The organizers said they had to draw the line somewhere.) Winners in the beverage categories include Basil and Blueberry Shrub from Blake Hill Preserves, Aeplz Cider from Coturri Winery, Perry from Finnriver Cidery, Fernet from Letherbee Distillers, Lemongrass Ginger Kombucha from NessAlla, and more. A number of New England regional delicacies were awarded, and I can vouch for their deliciousness. For this year’s announcement, Noma chef René Redzepi sent a congratulatory video, noting, of the winners:

“I believe it is our collective efforts that can turn the tide and ensure our shared earth will survive. You are the champions of the future, and you are leading the way.”

Thanks again. The video about the oven was heart (hearth?) warming!

Cheers, David!