Deirdre Heekin makes still and sparkling natural wines using fruit sourced from her home vineyard in the hills of Barnard, Vt., and from plots in the verdant Champlain Valley.

That fruit is not all grapes. Heekin, who with her husband, Caleb Barber, first launched La Garagista Farm and Winery’s fermentation projects two decades ago, views the category of “wine” holistically, generously.

Some La Garagista bottlings are indeed 100 percent grape, made from hybrid varieties like Marquette and Brianna that grow well in Vermont’s cold climate. Some bottlings mingle grapes with apples, either as a co-fermentation or by using pressed apple juice to kick off a grape wine’s secondary bottle fermentation. And some wines are all apple.

Below is an interview about those apple wines — most would call them ciders — that I conducted in July 2019 when I visited Deirdre while making a short film about Vermont terroir cider. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. I hope it makes you thirsty.

–

What do you say when someone asks, “What do you do?”

I say I am a farmer. I am a wine and cider maker. I am a writer. I am a photographer.

And after they scrape their jaw off the floor —?

Or I try to be those things! It’s like a practice.

—

What kinds of questions do they ask about your cider?

When I first started doing this, people would say, “Harvest is obviously really busy, but what do you do the rest of the year?”

There’s a lot going on the rest of the year.

Like what?

We have about fifty to sixty different fruit trees on the property — apple, pear, plum, and sour cherry, but predominantly different kinds of cider apple trees. They are very happy here. We’ve transitioned the orchard to, essentially, being in a meadow. We’re constantly adding new kinds of plants — broadleaf plants like comfrey and marjoram. We have daffodils that come in the spring, lemon balm, naturalized purple aster and valerian. We’re feeding that understory because these are all good companion plants for apple trees.

—

You manage your orchard — and your vineyard — biodynamically. What does biodynamics do for you? What does it give you in the bottle?

What biodynamic farming gives us in the bottle is undefinable, but, it’s there. I believe that you can taste it in the energy of the wine or cider. There’s this indescribable energy of the place where it’s grown. I think it helps refine, and focus, the terroir. I can’t give you scientific data for that — and I’m a big believer in science when it comes to biodynamics — only because we don’t have the tools to be able to talk about that right now. But I do believe that it exists.

In my previous life as a sommelier and wine director, I realized that the wines that I was choosing for my wine list all happened to be biodynamic. Again, it was not something that I could define or necessarily articulate, but it was there. It made a difference in the wine.

People principally think of you as a winemaker. Why do you also make cider?

Cider was supposed to be the quick and easy agricultural product that we could get out into the world early in the season — because the sustainability of your economics is an important part of being a farmer.

We had planted an orchard primarily for culinary purposes, and I hadn’t really thought of cider as wine in the beginning of my winemaking career, but the more I educated myself about the history of cider, I said, Well, it is wine.

—

What was your original inspiration for the cider?

Our former sous chef at our restaurant had heard that I was interested in cider and brought me some his own. It was one of the best things I have ever tasted. I said, “I want to know how you made that.”

He said, “I guess I have to take you to my grandfather.”

Our friend is part of an old, old Vermont family, and he arranged an adventure for us to meet his grandfather, Kermit, and taste his cider. The first thing out of Kermit’s mouth was, “Cider doesn’t get interesting until three years in the barrel, and it doesn’t get good until six.”

And I was like, great, there goes my whole idea of making a quick and dirty cider that comes out in early spring. Not at all! In fact, cider has become the longest-aging product, or wine, that we make.

What made that particular cider so special?

Historically in Vermont you picked your apples, you pressed them, you got the juice into the barrel, and you would pull off from that during the year, but you’d always save a little bit. You would never quite drain it, because after all we live in New England and we want to make sure we preserve some. Then the next season you would add new juice on top of what was left.

That’s one of the things that was making this family’s cider such an interesting drink. They were basically creating a solera system.

A solera, but with the live mother acting as pied de cuve for the next harvest, right? It’s also reminiscent of the use of reserve wine in Champagne.

Exactly. Really interesting. It was what was making this family’s cider such an interesting drink.

—

How did you adapt the process to your own cellar?

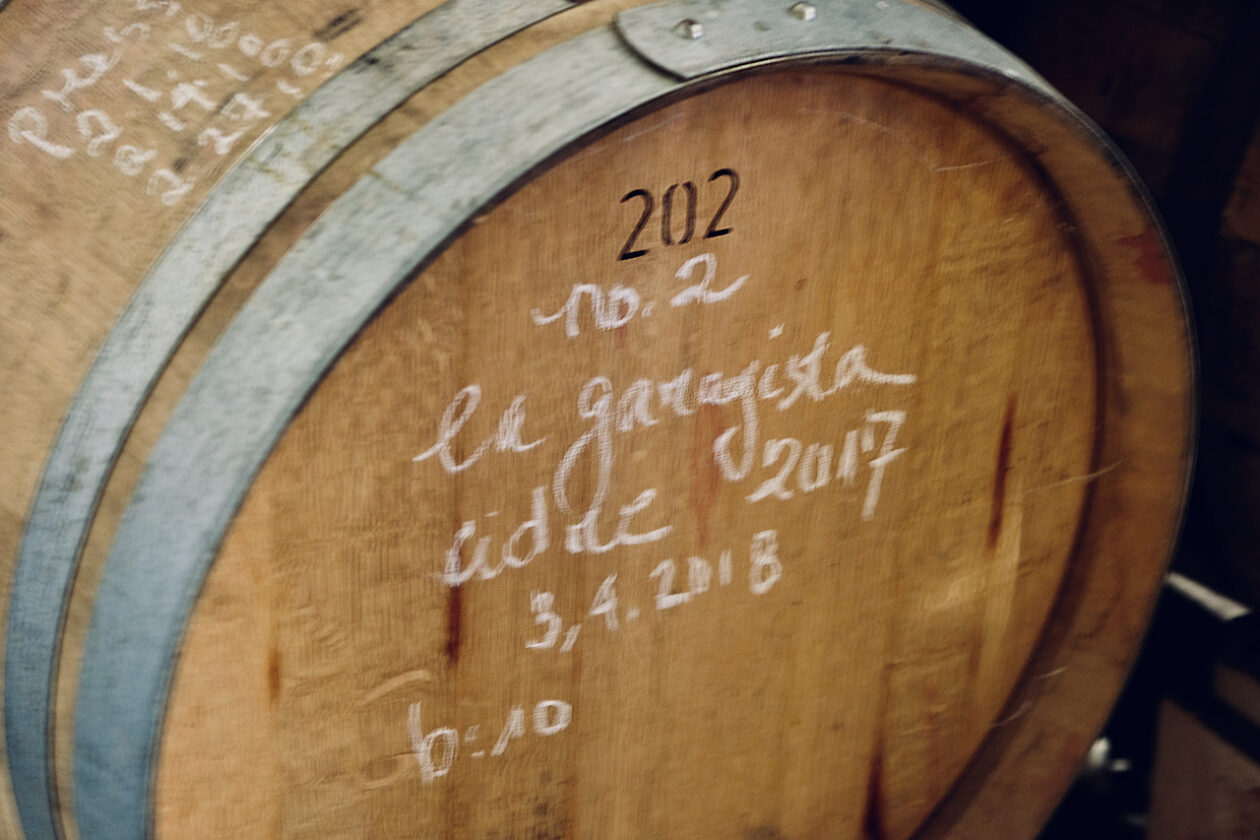

We started in 2010, and we didn’t release our first bottle until 2016. We have each of those subsequent vintages, and we’re treating it like a solera, with vintage upon vintage layered. It is part of what makes the wine speak volumes. It has this character that, again, is kind of undefinable. It also says so much about cider, and cider tradition, from this place, from Vermont.

Can you outline your process, step by step?

We pick the apples in November and store them outside on the crushpad so that for the first part of the winter they freeze, they thaw — freeze, thaw, freeze, thaw — and begin to condense their sugars.

In February or March, we thaw them for the final time and grind them in an old 1950s German hand grinder from Caleb’s parents. That goes into open vats where it ferments on skins for about four weeks, and then gets pressed in a bladder basket press, which is very messy because it’s like pressing applesauce by this juncture. This gives us the young, still fermenting wine, which goes into a barrel that has some cider from 2010 until now. It finishes and becomes a still wine within the barrel.

Also at the time of pressing, we’ll pull some of the juice and add it to the previous year’s wine. Then we put that in champagne bottles and cap it to have a second fermentation in bottle. So it’s a two-year process, essentially, for each vintage.

You’ve been using use “cider” and “wine” interchangeably. Why do you consider cider to be wine?

Because it’s fermentation. That process of taking a fruit and transmogrifying into a wine is the same for any fruit. My approach to cider is a really old, traditional approach, and is it just happens to be that fruit to make that beverage.

Of course there’s also a style of cider that’s more like beer. If you’re a craft brewer, you’re probably more interested in pursuing cider in that way. But I’m more interested in pursuing cider as more of a wine-like beverage. I like making the connection between wine and cider on the palate.

How would you describe the taste of your ciders?

I would describe them as “vinous.” You do get apple, but you get all of these tertiary flavors, a lot of salinity, floral aspects. It’s got a lot of texture and a richness. It has some volatile acidity, so it’s got these very high notes, but then there’s also a kind of deep earthiness. There’s a fair amount of minerality, which I think is unusual in younger ciders.

I feel like we’re starting to get more of a sense of this place, the things we’ve planted beneath the trees. In cider — like wine — as it ages, other elements are revealed.

—

Some people say, “I don’t like cider because I don’t like alcoholic apple soda pop,” and other people say, “I don’t like cider because I only like alcoholic apple soda pop.” How do consumers react to your cider?

They’re like “Wow, this is like wine!” We’re known as a winery with vineyards, and the people trying our cider are already thinking of our cider as wine, so we’re kind of in this rare and lovely position. We’re getting a very particular segment of the cider market — or the wine market.

We’re also in this niche of natural wine. I don’t like to put myself in a niche, but I think that other people definitely regard us as natural winemakers because we’re using spontaneous fermentation, we farm biodynamically, we use no to very little sulfur at our bottling, there are no additives in our wine.

I think of myself as a classicist. I want my wine to be classic. I don’t want it to be a style. This is a whole other conversation, but I think that natural wine has become equated with a style. But I think when you have unadulterated wine, and unadulterated cider, you can see the connections between flavor profiles between the two even though they’re made from two different kinds of fruit.

How do you like to serve your cider? What foods do you like to pair with it?

I like to serve my cider as an aperitif, throughout the meal. I serve it just like I would champagne or any of our other sparkling wines. All of our ciders are sparkling, they’re all second fermentations in bottle. They take a long time to make, so we revere them a great deal. I like serving them with anything like charcuterie — Caleb makes beautiful house-cured meats. I like it with some kinds of seafood, smoked fish, roast chicken.

Tell me about a cider project you’re working on right now that you’re excited about.

We have very prolific plum trees, and we had an opportunity to taste a beautiful plum and Riesling pét-nat in London. One of our interns, Madison, did a cider and plum sparkling wine, and when we opened it we were like, Okay, yes, this is a great thing to pursue.

She was also really interested in this idea of rose and apple. We have an extensive rose garden with a lot of heirloom roses, so we’re going to be experimenting with how to get the rose in the cider, whether that’s through a rose syrup that’s made with maple or honey, or a cider infused with rose petals. We’re not quite sure yet.

—

What kind of obstacles have you bumped into?

I have to say we’ve been really lucky. I’m crossing my fingers! I think my background making wine has helped tremendously in my approach to making cider. I’m not trying to learn from ground zero. I’m able to translate the things I’m doing in wine.

I can foresee rose being the biggest obstacle, just because it’s not a fruit that has its own fermentable sugars. We need to somehow infuse a sugar source.

Winegrowing in Vermont is a fairly new idea. Apple growing in Vermont is not a new idea. I’m sure people have asked you, Why make wine in Vermont?, but I want to know why you make cider in Vermont? What is it about making Vermont cider that inspires you?

I’m interested in making wine from all kinds of different things. Obviously, I love grape wine, but I’m also interested in apples, I’m interested in plums. I would love to make a sparkling rhubarb wine, champagne method. I like being able to approach these other fruits or flowers from a wine perspective.

There’s also this tradition of cider here in Vermont, this long-aging process for farm cider, that hadn’t really been explored yet. I felt like that was an inspiring and interesting tradition — and such inspiring cider when I tasted it — and it was something I wanted to do myself and educate people about, bring to the fore.

But I also believe grapes are strongly about Vermont. When I started, people said, “You should be making cider. You’re trying to force something.” The fact of the matter is that grapes are actually indigenous to Vermont and apples are not. Apples were brought here from England, France, Germany — but they have been here a long time.

Both are completely legitimate. Apples are part of our history here. They’re part of our terroir. They’re part of our story. So it is something that I believe strongly is about Vermont.

—

See Deirdre Heekin and other Vermont cider makers in our short film Vermont Terroir Cider: A Moment in Time.

Many thanks to Wine Business, Terroirist, and Wine Industry Insight for recommending this article to their readers. Top photo credit: Johannes Kroemer.

A great read Meg! I loved her response to your question about biodynamics!

Thank you for reading, Martin!