Orange wine is ancient wine. It originated, millennia ago, in the Caucasus, the stretch of land between the Black and Caspian Seas, where grape vines were first domesticated. Winemakers added white grapes to clay vessels, allowed them to ferment with their skins, and decanted a dark and savory wine.

Orange wine is modern wine. Winemakers, looking backward, looking forward, Janus-like, have made it all new again. Joško Gravner is one.

Note: You can click any story image to see it full size.

Gravner grows wine in the hilly extreme of northeastern Italy that kisses Slovenia. The Italians call this region Collio Goriziano, in Slovenian it’s Goriška Brda. Both mean “Gorizian hills.” From the winery, it is 500′ due north to the Slovenian border, which runs along a creek that bisects Gravner’s grapevines. On the Italian side, he farms the Runk vineyard, planted in 1901, and just past the creek are two more plots called Hum and Dedno.

He tends both red and white varieties, but is most famous for his orange wine of the white grape Ribolla gialla, which ferments for six months on skins in clay amphoras buried in his cellar. He’s credited with the reintroduction of the ancient style to Italy, and to the world. But it wasn’t always so.

From Traditionalist to Modernist to Postmodernist

Gravner is a third generation winemaker, Slovene by heritage. The given name on his birth certificate is Francesco, a vestige of the Mussolini era when it was forbidden to give a child a non-Italian name. The family first started bottling wine in 1973. Shortly afterward, Joško, then in his early twenties, took over.

At that time their vineyards were a gallimaufry of local and international varieties, including autochthonous grapes Ribolla and Pignolo and non-natives like Sauvignon blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot grigio, and more.

This was also the era that neighboring Friulian winemaker Mario Schiopetto began modernizing his own family’s white wine production, replacing wooden fermentation tanks with sleek stainless steel, managing fermentations with cultured yeasts and temperature control, and bottling crisp white wines to please international palates.

Young Gravner joined the bandwagon. He jettisoned his family’s old wood aging casks, replacing them first with concrete and later stainless steel. In the 1980s he acquired French barriques. His techniques produced wines with ripeness and polish, and soon they, too, were commercially successful on the international stage.

In 1987, Gravner visited California to take a deeper draught of the modern style. To his surprise, the experience left him cold. He was struck by how many additives and interventions were in play, and it got him thinking about his own processes. His wines were good, just not good enough. And they were a lot of work to make. Chardonnay in Collio, when ripe enough to vinify, produces a wine at 17.5% alcohol. It takes a lot of tinkering to bring a wine like that into balance, and then it ends up tasting no different from a Chardonnay made in California.

Gravner also began to realize the older, local grape varieties of his forebears, grapes like the Pignolo, Refosco, and Ribolla still resident in his vineyards, usually performed much better, with far less fuss.

“Wine should be as simple as possible,” Gravner told me when I visited him in Oslavia, in June, speaking in Italian interpreted by his daughter, Mateja Gravner. “You should not use every process just because you have the option to use more than 300 additives. I prefer to drink water.”

“Ribolla is very balanced in our area,” Mateja said. “So why should you fight to have balanced international wine when you could have a local wine which gets balanced by itself?”

The Mother of Invention

To move forward, Gravner looked backward. Prior to World War II, Friulian winemakers often fermented Ribolla with its skins. The style faded in the post-war period, abandoned in favor of a brighter modern style. Gravner began researching the skin-fermented winemaking tradition of the Caucuses, where they use large buried clay vessels called qvevri, to understand how the process might be applied to his own territorio.

“The unique and important thing is that to make wine, you should always look for what was in the past — but not for nostalgia,” he said. Rather, for inspiration, for technologies and philosophies that could be adapted to contemporary winemaking.

Wine is fluid in many senses of the word, a liquid in flux. Older prototypes — orange wine, port wine, barrel-aged reds, sparkling wines — are passed through generations, written in chalk marks on cellar walls, in grease marks on casks. Today’s winemakers can draw inspiration from these stonewashed narratives, but also from the Scott Labs book. Such a modernist mindset applies equally whether one’s making supermarket Chardonnay or small-lot farmer fizz. The point is that wine evolves, but not in pre-ordained evolutionary next steps. History sets the mise-en-scène, but doesn’t write the script.

In the mid-1990s, following both research and intuition, Gravner began tinkering with skin-contact fermentations of Ribolla. Then in 1996, hailstorms destroyed nearly his entire grape crop. Figuring he had nothing to lose, he took what Ribolla grapes he could salvage and divided them into four experimental barriques. Two had skins and two had just juice. Into one of each type he added commercial yeast (hello, Scott Labs book), and left the other two to ferment naturally.

Six months later he got a first taste. “In spring 1997, he tasted the Ribolla fermented on the skins with no added yeast, and he recognized in this very young, not complete wine, he tasted the Ribolla grape,” Mateja said. “If you taste the grape, and you taste the wine, the wine should taste similar.” He had turned a stroke of bad fortune into a stroke of genius.

The following year, Gravner got his hands on a 250-liter amphora from Spain and used it to make a small amount of skin-contact Ribolla in clay. The wine macerated only four days — not long by current orange winemaking protocols — and he lost some wine because the vessel wasn’t lined with beeswax. But the results were more than encouraging.

All-in for Amphoras

In 2000, Gravner finally had a chance to travel to Georgia, not to visit with winemakers, because at the time only monasteries had cellars. Instead, he went to find a qvevri producer and order vessels. The manufacturers were completely unaccustomed to filling orders from winemakers outside of Georgia, yet Gravner ordered eleven large amphoras to arrive in time for the 2000 harvest. Nine of the eleven arrived broken — in November.

So 2001 was Gravner’s first Ribolla vintage to be partially fermented in amphora. That year, he let the wine spend three months on skins before pressing it off to age longer in wooden tanks. Over subsequent harvests, as he built his amphora cellar (and the qvevri producers figured out how to ship them intact), he also developed his process. He allowed the skins to stay in contact with the juice for longer periods, and let the wine age longer in the cellar before bottling, too. Currently, from harvest to release is an astonishingly long seven years.

The Proof of the Pudding

After this transformation, some of his peers thought he’d gone insane. A few found the wine undrinkable. Why would he throw away prior success to pursue such an old-fangled technique?

“There are two approaches in winemaking,” Gravner told me. “First: understanding the demand and following the market. And second: just doing the wine. I prefer the second path, producing the wines I like.”

Today, Gravner’s aging process for the orange Ribolla mostly follows a Rule of Six: six months in amphora on skins, six months in amphora without skins, six years in large wooden tanks, and six months in bottle before release. Any given step is little shorter or longer depending on the vintage, but Four Sixes is a handy mnemonic.

The result is a dark orange-amber wine redolent of dried apricot, sultana, and acacia honey. Fully dry, it is a textural, savory wine that’s outstanding with the region’s cuisine featuring venison, Prosciuitto, cheeses, smoked freshwater trout, and other foods from the forested hillsides. (Find tasting notes on four Ribolla vintages below.)

Just don’t call it “orange.” Despite meeting me in an on-brand orange polo shirt, Gravner prefers the term “amber.” “The color amber is a living, lively, healthy color,” he said. “Orange in the wine world doesn’t have a good connotation, because it’s the color of a wine in decline.”

Unfortunately, the “orange” ship has sailed.

A Love of Territorio

On the day I visited, the air was hot and muggy but there was a gentle breeze. The winery is located 20 km from the sea and 45 km from the mountains, so the air stays fresh. The wind can become extreme in winter, when the powerful winter Bora, which can reach speeds up to 160 km/hour, torments the vines. Cypress trees here serve as wind blocks.

The vineyards are planted to a diversity of species, not just grapes but also fruit and nut trees, grasses and flowers. There are 300 bird houses on the property to foster both quantity and diversity of birds. Each of the three vineyards also has a pond to attract wildlife. These are home to many frogs, invisible until they jump!

Some might question the wisdom of inviting birds into a vineyard, but the Gravners find their presence is a boon to biodiversity. “Birds eat fruit when they’re thirsty,” Mateja said. “Not when they’re hungry.” Hence the ponds.

Most of the international grape varieties are gone now, pulled to make way for the ancient local vines. But since all of Gravner’s wines age for many years in cellar prior to release, some of those grapes still repose in bottle. In Collio, I tasted the 2009 Bianco Sivi, a dark amber wine that’s not your grandmother’s Pinot grigio. There’s also a white blend, 2012 Bianco Breg, that contains a medley of grapes: Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc, Pinot grigio, and Welschriesling.

In the Runk vineyard, on the Italian side near the winery, there are rows of Ribolla and Pignolo, the Ribolla trained into a modified bush vine called alberello in fila, which makes the trunks look like the Greek letter Psi (see the illustration toward the top). This training system, implemented on the recommendation of agronomists Marco Simonit and Pierpaolo Sirch, allows the fruit to develop closer to vine wood, which they claim produces better fruit. The system also trains the vines into neat but narrow rows, allowing a small tractor to pass through the vines. Disease pressure from oidium and mildew makes it necessary to treat them with organic controls.

Red Pignolo is a picky grape — Mateja calls it a spoiled child — but it makes a great red wine, deep garnet with flavors of cherries, black raspberries, and plum, a mix of darkness and light. “In Friuli, we have four autoctono red vines,” said Gravner, “Refosco, Tazzelenghe, Schioppettino or Ribolla rossa, and Pignolo. Pignolo is the one I find most satisfying. Pignolo as a red wine is very difficult, but I want Pignolo anyway.”

These red grapes, along with three whites — Ribolla gialla, Tocai, and Malvasia — are the soul of the region, said Gravner. “Having such an incredible variety, why waste it?” he said. “If I were the big boss in Friuli, I would allow only planting these three whites and the reds. Instead, everything is planted here. I don’t like that Oslavia is the country of Ribolla, but you still have Chardonnay, Pinot grigio.”

Ideally, he’d like to see local grapes become so closely associated with the region they melt together into one thing, territorio. “Not soon, but in future years, we could have a village with Ribolla being like in Burgundy, where they grow Chardonnay but they don’t call it ‘Chardonnay.’ The Chardonnay is called by the place name.”

Ever Onward

“I’m happy that new generations of winemakers are working toward natural wine, and avoiding chemical processes,” Gravner said. “I appreciate the wave of wine producers that are returning back. I make wine for myself, for my personal consumption, and if there’s excess I sell it — and I don’t drink wine every day,” he said.

I asked Gravner what’s most in his way right now, and what he might change. “I wouldn’t change anything, except to make the process better year after year,” he said. “Every year you find something you can do better, in a better way. This is the challenge every year for me.”

I kept probing. You’re an innovator. There must be some idea you’re working on next, something you’re planning?

“It’s spontaneous,” he said. “This isn’t something you can teach or learn. It’s a kind of intuition, but always supported by good technical knowledge.” After that disclaimer, he proceeded to blow my mind.

“So the thing I’m working on is a cellar with glass — big glass vats, huge ones. The idea is to have the wine, after the first year in qvevri, spend two or three years in wood tanks and the rest of the aging in glass.”

Glass vats?

“My father, years ago, told me there are only two materials for wine: wood or glass. I added the third one, terracotta.” His objective is to age the wine in a mix of all three, ideally reducing the overall élevage time. “In order to shorten the six years of aging, it would be half in wood, more or less, and half in glass,” he said. He’s still working it out, and won’t really know until it’s all right in front of him.

The inspiration is drawn from floating glass swimming pools (there’s one at Embassy Gardens in London). Why not one that’s food-safe, and built for a cellar? It’s just a matter of finding someone to make it.

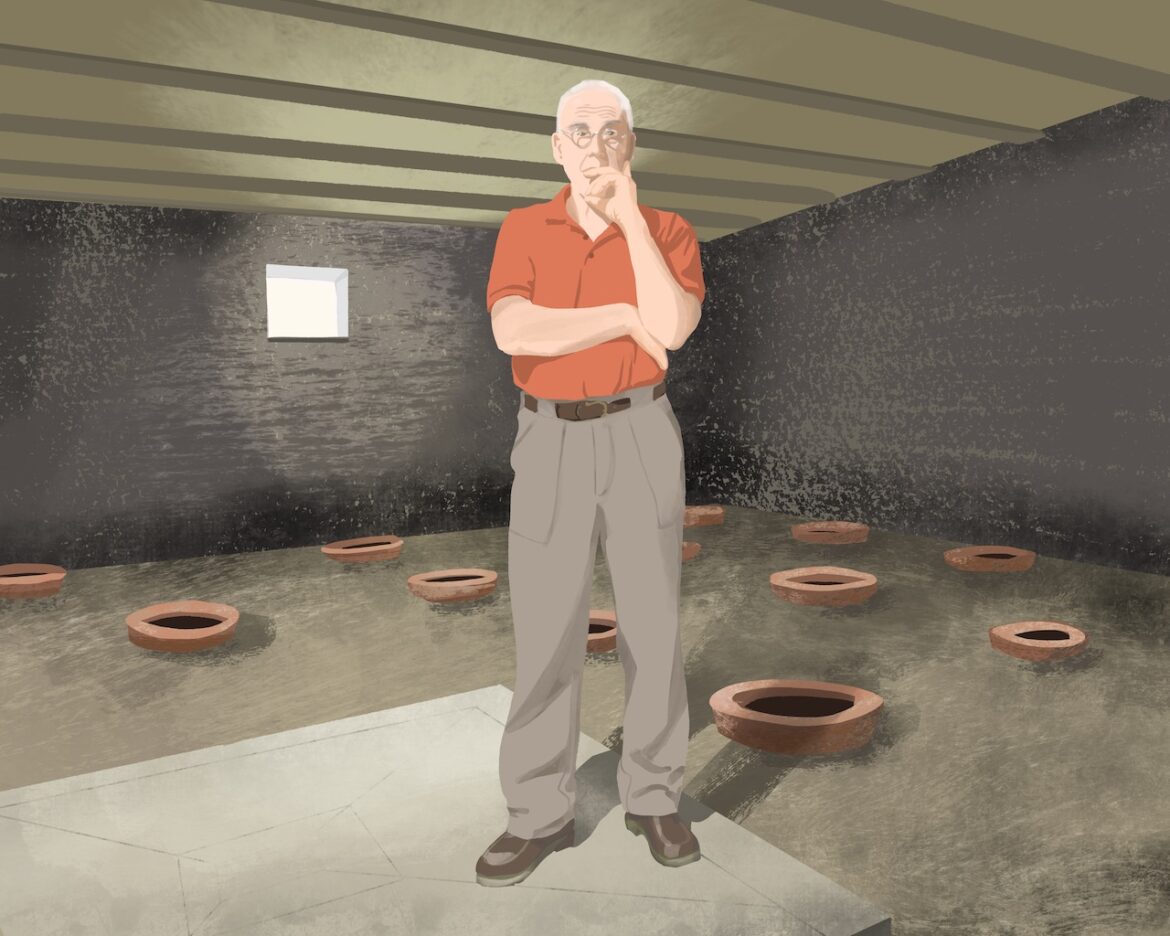

“The cantina is being prepared for this glass tank already. It’s completely underground.” Gravner walked us over to the spot in the cellar where these notional tanks will be installed, waving to the empty cement room stained with age, his shadow dancing off the walls.

I asked him if he would start small and test, as he did with the original skin contact experiments, or go all-in for a whole vintage.

All of it, of course. “When he’s convinced about something, he’s 100%,” Mateja said. “It could take years, but once you dream, dream it big.”

I wished him “buona fortuna” — Good luck!

He smiled back at me with bright eyes. “La fortuna è la cosa la più importante,” he said. Luck is the most important thing.

Tasting Notes

2009 Gravner Ribolla Venezia Giulia IGT

14% ABV — High-toned fragrance of sultana, dried apricots, yellow apple, and light honey. The wine opens and becomes more honeyed as it sits in the glass. The palate is textural, drying, with a blaze of acidity, especially in the mid- and late palate.

2011 Gravner Ribolla Venezia Giulia IGT

15.5% ABV — The fruit notes are quieter, more restrained than the 2009, but the wine also has a darker, countenance, more brooding, more acacia or forest honey than light honey. This is a powerful wine, from a ripe vintage. Mateja said this one is Joško’s favorite.

2013 Gravner Ribolla Venezia Giulia IGT

14% ABV — Spirited aromas of fresh and dried apricot. The fruit is vibrant and the texture is rounded, velvety, with fully integrated tannins. The finish is shiny-bright.

2014 Gravner Ribolla Venezia Giulia IGT

14% ABV — Fragrant of dried peaches and pears; it’s the most floral, with a pleasant note of brushy greens. The texture sits in contrast, with drying tannins and a darker overall mien. It’s a complicated mix — just like its maker.

Artist/author’s note: It seemed fitting that an interview with a winemaker famous for handmade wines should be illustrated with hand-drawn images. I made these illustrations using my own photographs as inspiration, but the compositions are original. My tools are iPad Pro 12.9″ fifth generation, Apple Pencil second generation, and the app Procreate v. 5.2. Like all material on this website, these images are copyright Meg Maker and their use in any medium without permission and attribution is not allowed. Please contact me about licensing, usage, permissions, or to discuss a new commission. Thank you!

My visit was part of a media tour organized by Studio Cru. All travel and hospitality expenses were paid by their clients, and all wines were samples for review.

Many thanks to Terroirist and Alder Yarrow of Vinography for recommending this article to their readers.

I’m grateful to Mateja Gravner for her kind attention over two and a half days, to the Sirk family of La Subida for their gracious hospitality, and to Joško Gravner for his generosity of time and mind.

Magnificent! I buzzed through it quickly and was so impressed with the overall storyline and illustrations. Now I will go through it more thoroughly and savor it. Great work!

I mean, if Mom doesn’t love it, who will?

So impressed you did the illustrations as well. Congratulations! And, now I must try orange wine!

Thank you, Andrea! Orange wines exist in many styles and hues, from light to dark, faintly grippy to savory. I find them really food-friendly, because they combine the fruit flavors of white wine with the refreshing textural tannins of red. Ask your favorite wine shop for some examples to try, and let me know what you think!

Meg: Very nice information and illustrations!!! A cut or more above!!!

Thank you, John!

Interesting read, thanks. The Sky Pool is made of acrylic though, not glass.

Good to know — thanks! They mentioned a sky pool in Dubai made of glass, but I wasn’t able to find evidence of one.