Lunch was long over. I’d thanked my host, gathered my knapsack and coat, and ventured outside to await my van. I waved off two colleagues as they greeted their own driver before disappearing in a plume of dust.

A cloud moved above and I cinched my coat. I sat to wait, looking out across the springtime vineyard. The terrain here was rolling and generous, more open than other sceneries I’d visited. Umbrian terroir is a mosaic of hills and plains that generates dramatic skies.

Twenty minutes passed and still no van. I texted the organizers to ask for news. A winery employee cracked open the door. “Tutto va bene?” Everything okay?

“Non lo so—?” I ventured. My Italian is weak but I try. “Ho avvisato il consorzio. Aspetterò un po.” I’ll wait just a little longer.

Forty-five minutes, then an hour. Danilo Antonelli, the winemaker of Valdangius who’d hosted my lunch, rounded the corner of the yard, startling at the sight of me. I shrugged, my eyes a question mark.

He gestured to his small car. “Andiamo!” he said, “I drive you.” He surely had better things to do than ferry an American journalist into town. I tried to protest, but his daughter hopped into the back seat as he motioned me into the front.

The landscape rolled by as my brain fumbled to formulate small talk. “Quanti minuti a Montefalco?” I asked.

“Dieci,” he said. Only ten.

More silence. I could see smoke rising from some vineyards, perhaps from workers burning vine cuttings. More formulating. “I lavoratori tagliano le vigne?” I had no idea whether this made sense. I hoped the verb I’d chosen, tagliare, was used equally for vines and pasta.

“Si,” he nodded. Perhaps he is more garrulous in Italian, or after a glass of his excellent wine.

Soon we were mounting the hill of Montefalco, pulling onto the stone cobbles of its central plaza. I disembarked with effusive thanks. Danilo smiled modestly, his daughter waved, and they were gone.

I had arrived in Montefalco three days earlier, my visit timed with Anteprima Sagrantino, the release of the 2019 DOCG wines to market. This historic hilltop town lies roughly in the center of Umbria, and its five thousand inhabitants populate stone dwellings that spill down its flanks onto a skirt of agricultural landscape. Umbria is known as “the green heart of Italy,” and its undulating terrain is carpeted with farmland, vineyards, olive groves, and forest. It is one of the nation’s few landlocked regions and is, in fact, the only one that lacks either an international border or a salty rim of sea. Umbria, in other words, is the only Italian region completely surrounded by Italians.

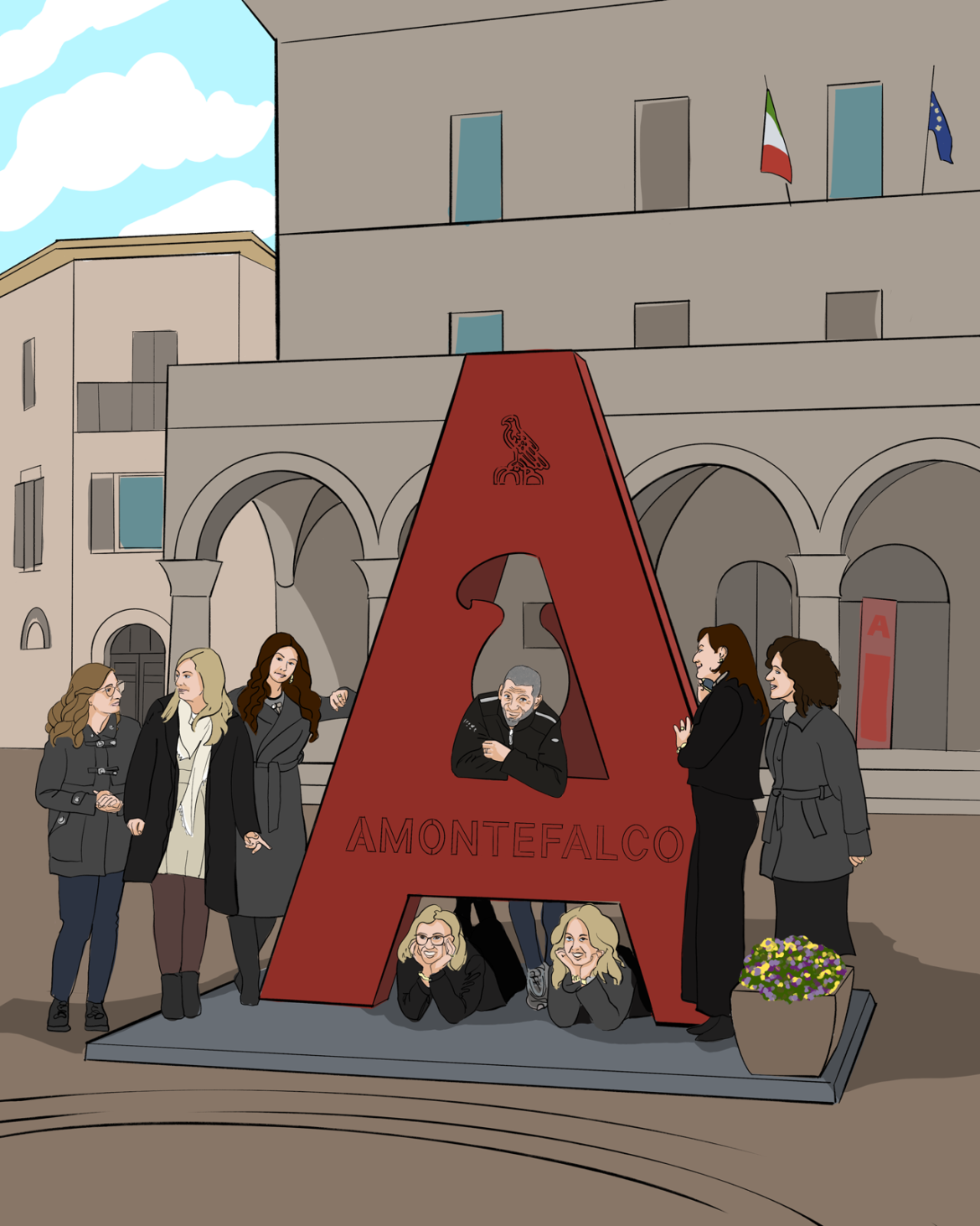

The center of Montefalco is ringed with civic buildings, hotels, and cafés, and in the midst of its grand circular courtyard the Consorzio Tutela Vini Montefalco had erected a giant letter A. This sign, I learned, stood not only for Anteprima but also A Montefalco (“in Montefalco” or “to Montefalco”), a slogan they’d coined to suggest that the week’s shenanigans were not merely a taste but an immersion.

Scores of other international journalists had likewise been invited for the program. We’d been furnished with a list of the 42 participating wineries and tasked with constructing a personalized itinerary of up to five winery visits per day. I’d found this assignment bewildering, partly because I had little familiarity with the producers, but mostly because the logistics seemed utterly incomprehensible.

Then I learned that the organizers had commissioned a bespoke smartphone app to manage the complexity, and so, theoretically, journalists and winery hosts and sundry chauffeurs needed simply to check our phones to figure out the next Who, What, and Where. It was a brilliant concept, and on the first day it worked flawlessly. But all apps are works in progress, and this one unraveled spectacularly on Day Two, resulting in skipped connections, missed appointments, and lonely journalists scattered across the territorio. No matter. In the end we all found our way back town, soothed by the balm of Italian hospitality.

I’d also arrived in Montefalco with a few preconceptions about Sagrantino. It is a difficult grape, aggressively tannic, arguably the most so of Italy’s two-thousand-plus native vines. Growers must let the fruit hang as long as possible to ripen the tannins, so harvest generally floats into October. This is a delicate balancing act, because fruit sugars can bloom out of control, and even cautious handling produces a wine with alcohol of 14.5% and higher. In youth, Montefalco Sagrantino can be boisterous, even rasping, its armature of tannins unyielding, so cellaring and bottle age are required to reveal its violet-fruited charms. It hits a sweet spot at eight or ten years, blossoming into a wine with earthy complexity, a core of brambly fruits, and the musculature needed to balance Umbria’s generous cuisine.

The Montefalco consorzio, acknowledging the strategic limitations of showcasing overtly youthful wines, had expanded the Anteprima’s scope to include the region’s Rosso wines along with a fresh cast of whites, pinks, and sparklers. There were also plenty of aged Sagrantinos available, both at the wineries and in a tasting salon staffed with a corps of professional sommeliers.

Sagrantino has not been produced as a dry varietal wine here for very long. Wineries only started bottling it in earnest in the late 20th century, and it was granted DOCG status in just 1992. Previously the grape was used largely for sweet passito wines that were traditionally served at the Easter feast (sagra). “There is not a long tradition of winemaking of Montefalco Sagrantino,” said Nazareno Pieroni, cellar master at Di Filippo winery in Cannara, when I visited him on my first day’s outings. Locally, red table wines were blended. “Montefalco Rosso was the wine you drank in the osteria,” he said. Today, that blend is predominantly Sangiovese, with Sagrantino, of course, and, sometimes, international grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot. It is accessible and friendly, the juicy, easy-drinking counterpart to its broad-shouldered big brother.

“Sagrantino is very complicated for people who don’t drink a lot of Sagrantino,” said Massimo Giacchi, winemaker at Le Thadee. He is in charge of this newer winery that sources fruit from six hectares around Montefalco, including a patch of own-rooted, pre-phylloxera vines. He’s trying to change the overall character of the grape, to tame its rustic reputation. “Sagrantino is a strong wine, and this project is for delicate wine,” he said. To create that desired finesse, he’s chosen to age his Sagrantino in large Italian clay anfora, atypical in a region that has long relied on oak cask. He likes the clay’s smoothing effect. “Terracotta is a live container,” he said. “The wine is in contact with the air, with macro and micro oxygenation. It changes the sensation.”

Luca di Tomaso, with his eponymous young label, prefers cement tanks for both vinification and aging. It’s a material that behaves in some ways like clay, delivering modest oxygenation with no oak flavors. “I believe in concrete,” he said. “You can feel the difference between steel and concrete in the nose, the perfume. The stainless steel is reductive.” Even so, there’s a handful of old oak barrels and stainless tanks in his tiny startup winery; one uses what one has. I found his Rossos and varietal Sagrantinos wildly aromatic, with floral and herbaceous notes (roses, oregano, rosemary), plus blackberry and currant fruit and smooth, tea-like tannins.

Di Tomaso started his project in 2016 and now sources grapes from ten hectares of organically certified vineyards, producing only twenty thousand bottles per year. At that scale, small mistakes in the vineyard or winery, or even just a stretch of unlucky weather, can be calamitous. “There is no roof,” he said, waving his hand at the vastness of sky. “You can feel every vintage in a small cellar. Maybe in a big cellar they can put in ten percent of something else, but here we can’t do that.” He’s worried about climate change, especially given Sagrantino’s tendency to generate abundant sugar in heat. As it is, “alcohol at 13% and 13.5% here is not possible,” he said. “For every DOC in Italy — Barolo, everywhere — it could be a bad problem. In five to ten years you can’t have a wine at 12% to 13% — white, too — if you don’t add water.”

At Le Cimate, winemaker Paolo Bartoloni addresses Sagrantino’s boisterous tannins simply by holding onto his wines longer before release. “For me, anteprima is a dream!” he laughed — meaning pipe dream. He was showing (and currently selling) 2016, while 2017 was about to be bottled. Both his 2016 and 2015 revealed ample plummy fruit, with grippy but sueded tannins and a lift from rose petals and black tea. Bartoloni likes to throw a few other tricks at this iconic grape, for example blending it with Cabernet Sauvignon to make a “Super Umbrian” that he ages in American oak, and also nodding to its passito past by producing a wine with one-third raisined grapes.

But even as he tinkers outside the boundaries, he advocates for formal changes to the DOCG. “We need to create a Sagrantino Riserva,” he said. “We all produce it, but with different names.” He thinks seven years is the right duration. “Barolo, Chianti, they have riserva, but we are the most necessary land to be riserva, because we fight with the tannins.” While it may be a good idea to formalize this style, the wines would necessarily be pricier, and given that it’s not hard to pay $50 and up for the normale, the market may need convincing about the value of riserva.

At Fongoli, I traipsed through the biodynamic vineyards with Ludovica Fongoli, who with her father, Angelo Fongoli, crafts sincere, old-fangled wines. I admired the fruit and olive trees and a pair of docile draft horses who regarded me with curiosity. We stomped out to a small plot of vines trained in the historic palmetta system, which is reminiscent of the orchard trellising technique of espalier, with four to six horizontal cordons trained along tall wires. This traditional approach was phased out of production in the 1980s due to its low productivity, but Fongoli prizes these very old vines, bottling a vineyard designate of them called Fracanton.

“The most important thing we do is work in the vineyard,” Angelo Fongoli said, once we were back at the winery and working through the tasting. “We focus on diversity, on spontaneous grasses cut very high to allow them to make flowers and seeds. We don’t do the same work every year. And we don’t prune for the vineyard, but for the single vine.” Fracanton does not have DOCG status because, according to the consorzio tasting panel, it had both a touch of Brett and too much oxidation. Fongoli shrugged. “They want all the Sagrantino to be the same, every cellar,” he said. I lingered on its savory blackberry fruit and beautifully integrated, powdery tannins. This wine is Fongoli’s apotheosis, he said. “We like to produce Fracanton because it’s the wine most close to the wine we produced fifty years ago. It’s the best wine we can do.”

Montefalco is not all dark and brooding reds. Nearly every producer I visited also makes white wine, mostly using local Trebbiano Spoletino and Grechetto grapes, varietally or as a blend. They can be refreshing with notes of herbs, tree fruits, and a touch of honey, and pair especially well with regional first courses: crostini, salads, spring soups, burrata, risotto. Many make rosé, from Sagrantino, Sangiovese, or international varieties, and some are also tinkering with orange or amber wine. At La Fonte, a winery and agroturismo run by siblings Francesco and Giulia Trabalza Marinucci, I enjoyed an amber Trebbiano Spoletino (with twenty-five days of skin contact) with a glorious plate of hand-made gnocchi with pecorino and saffron. (Giulia is an outstanding chef, and that lunch was the best meal I ate in the region, hands down.)

A number of producers also make sparkling wines, both white and rosé. Scacciadiavoli produces a traditional method Brut from Chardonnay and Trebbiano Spoletino, and a Brut rosé from 100 percent Sagrantino. Remarkably, the white was the bigger wine, rounded, with substantial structure and savoriness. Danilo Antonelli of Valdangius (my hero with the car) produces a charming undisgorged pét-nat of Trebbiano Spoletino.

But I did find two red-only projects. Lungarotti, an historic family which also has an estate in Torgiano, Tuscany, produces only Sagrantino at their Montefalco location. Export and marketing manager Marco Rossi, who led a tasting of wines from both properties (don’t tell the consorzio), said the goal is to make “polite and educated wines” that shake off the region’s reputation for rusticity. “Our wines don’t shout, they whisper,” he said. Their Rossos were fruit-forward, and their 2019 Montefalco Sagrantino, now in the market, was eminently drinkable, its core of sweet dark fruit and chewy tannins wound with a perfume of brushy herbs.

Similarly, the Lunelli family, which also has estates in Trento and Tuscany, focuses on Sagrantino at Tenuta Castelbuono, their Umbrian property. (See my notes from visiting their Villa Margon in Trentino, where they produce Ferrari sparkling wines.) Alessandro Lunelli, the youngest of the four Lunelli siblings running Tenute Lunelli, and head of the effort in Montefalco, hosted a reception and dinner for all of us under the dome of their unique, shell-like facility, Il Carapace, designed by Italian sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro. In addition to Montefalco Sagrantino DOCG, they produce a Rosso and Rosso Riserva DOC, along with a sweet passito. I was also able to taste a limited bottling Montefalco Sagrantino “Lunga Attesa,” a selection of their best vines. I found all of their wines polished and stylish, with smooth, precise tannins and brilliant fruit.

With such a large number of participating producers, it was impossible to taste all of the wines, or even all of the wines I wanted to taste. As usual, I focused principally on producers who follow organic, biodynamic, and sustainable agriculture, heartened by how many have chosen to work this way. But even with advance planning, I was unable to secure some desired appointments and had to settle for tasting the wines in the salon rather than meeting with principals. Notably absent from all proceedings were the wines of Paolo Bea, beloved of sommeliers and priced accordingly. I’d only ever had a few drops of them — literally, at a walkaround where the importer’s pours were beyond parsimonious. The winery has since appeared in the Consorzio’s producers list, prompting speculation about discord and harmony, and fueling hope if I return.

I came away from Montefalco with a fresh appreciation for this heritage grape, and an admiration for the families who are committed to its legacy and future. It can be tempting to cast autoctono grapes in amber, cherishing them as historic relics to be preserved rather than contemporary foods to be savored. My experience in Montefalco was further proof that styles evolve, producers love to tinker, and drinkers love to taste. Montefalco Sagrantino is an ongoing experiment, one that, at least until climate chaos renders the grape untenable, invites us into its firm embrace.

I’m grateful to the Consorzio for sponsoring my travel, and to Miriade & Partners for their coordination. All wines were samples for review.

My original illustrations are inspired by my experiences, impressions, and photos from my visit. Like all material on this website, the images are copyright Meg Maker and their use in any medium without permission and attribution is not allowed. Please contact me about usage or to discuss a new commission. Thank you!