Port winemaking in the Douro Valley is centuries old. It has persisted through seismic historical developments in Portugal, from the fall of Empire to the ravages of phylloxera to global economic upheavals. Today, Port confronts a fresh set of problems as the climate warms, sweet wine sales slump, and the landowning families grapple to reconcile legacy with growth.

I’ve twice traveled in the Douro to visit Port producers at harvest time. My goal was not only to taste the wines but also to examine the machinery of terroir, the social, environmental, and emotional forces at play. Port winemaking is complicated business, a modern enterprise that nonetheless clings to remnants of its pre-industrial past.

Image-making is a ruminative process that brings me closer to my subject and its salient themes. In this visual essay, I’ve tried to convey these complexities and entanglements. I hope these words and pictures enrich readers’ understanding as we all contemplate the future of Port.

David Guimaraens is technical director and head winemaker for Taylor Fladgate, and Robert Bower is the company’s export manager. Both men descended from port winemaking families; they are in the sixth and eighth generations respectively. Guimaraens, who said he started work at age eight, has contributed several innovations to the field: a new formula for the fortifying brandy, a rosé port called Croft Pink, and mechanizations that make swift work of ruby and nonvintage wines. Douro winemaking is “mountain viticulture in a hot climate,” he said, and mingles variables of site, elevation, and aspect with ten-plus grape varieties. “All these variables come together in the magic of Port.”

Taylor Fladgate is credited with inventing, or at least popularizing, white Port in the early 20th century, but now it’s produced by many houses. Essentially a lighter, more refreshing line extension, white Port is made from local grapes like Malvasia, Rabigato, and Viosinho and fortified to 20 percent ABV; it generally sees no wood aging. White Port is served chilled or over ice, often mixed with tonic water, citrus, and mint for a low-alcohol cocktail affectionately called a “portonic.”

There is a railroad along the Douro, and its completion in the 19th century was a lifeline for producers who had previously depended on the river to transport wine downstream and supplies up. I’ve taken that train, but it gets one only so far. The wine estates are not sited for convenience, and a car is required for the last leg. The road is pitched, steep, and vertiginous, the switchbacks torture to the dyspeptic. The view is worth it.

Port is not one thing, it’s many. There’s ruby, tawny, vintage, late-botted vintage, single-quinta vintage, colheita, crusted, pink, and white. I may have missed some. The dizzying mix of styles offers something for everyone, yet Port’s market position is not guaranteed except at the highest end. Portugal’s population is aging and shrinking, and the Port industry relies on exports for its lifeblood. The last few years have seen an uptick in some key markets, for example the U.K., while others like US, China, and Japan, were flat or fell. Many producers have ramped up production of dry table wines, both white and red, to keep land in vine, their partner growers viable, and to offer yet more options.

In the late 1860s, phylloxera marched up the Douro Valley, wiping out vineyards and driving farmers off their land. The expense of replanting was too great, and many of the hand-built stone terraces, carved into the riverbanks to give both vine and worker stable footing, fell into ruin. Some owners moved to Brazil seeking fortune, and some returned later to replant, tinkering not only with grapes but also mulberry for silk production and olive groves for oil. Yet many pre-phylloxera properties remain abandoned today, their buildings now husks crumbling into the granite landscape, their vineyards overgrown with brush.

Port has generated family dynasties. The Symingtons trace their lineage to ancestor Andrew James Symington, who emigrated from Scotland in 1882 and swiftly established himself as a Port shipper, soon also marrying a woman descended from Port merchants dating to the 17th century. Third-generation James Symington began working for the firm in 1960; he helped expand the U.S. market and stabilize the company during difficult economic periods, and also renovated an abandoned estate near Pinhão into a working vineyard and residence, Quinta da Vila Velha. (James Symington died in November of 2020.) James’s son, Rupert, joined the company in 1992 after working in finance; he became CEO in 2019 when his cousin, Paul, retired. His wife, Anne Symington, is originally from San Francisco. When their son Hugh joined the company, he initially worked in the U.S. for the firm’s importer, Premium Port Wines, but in 2021 assumed the role of marketing and communications manager. This story, with different dramatis personae and plots, could be told of many Port families. While not everyone wants, or secures, a spot in the business, and many work elsewhere before returning, the persistence of such multi-generational corporations suggests kinship ties have been critical to Port’s endurance.

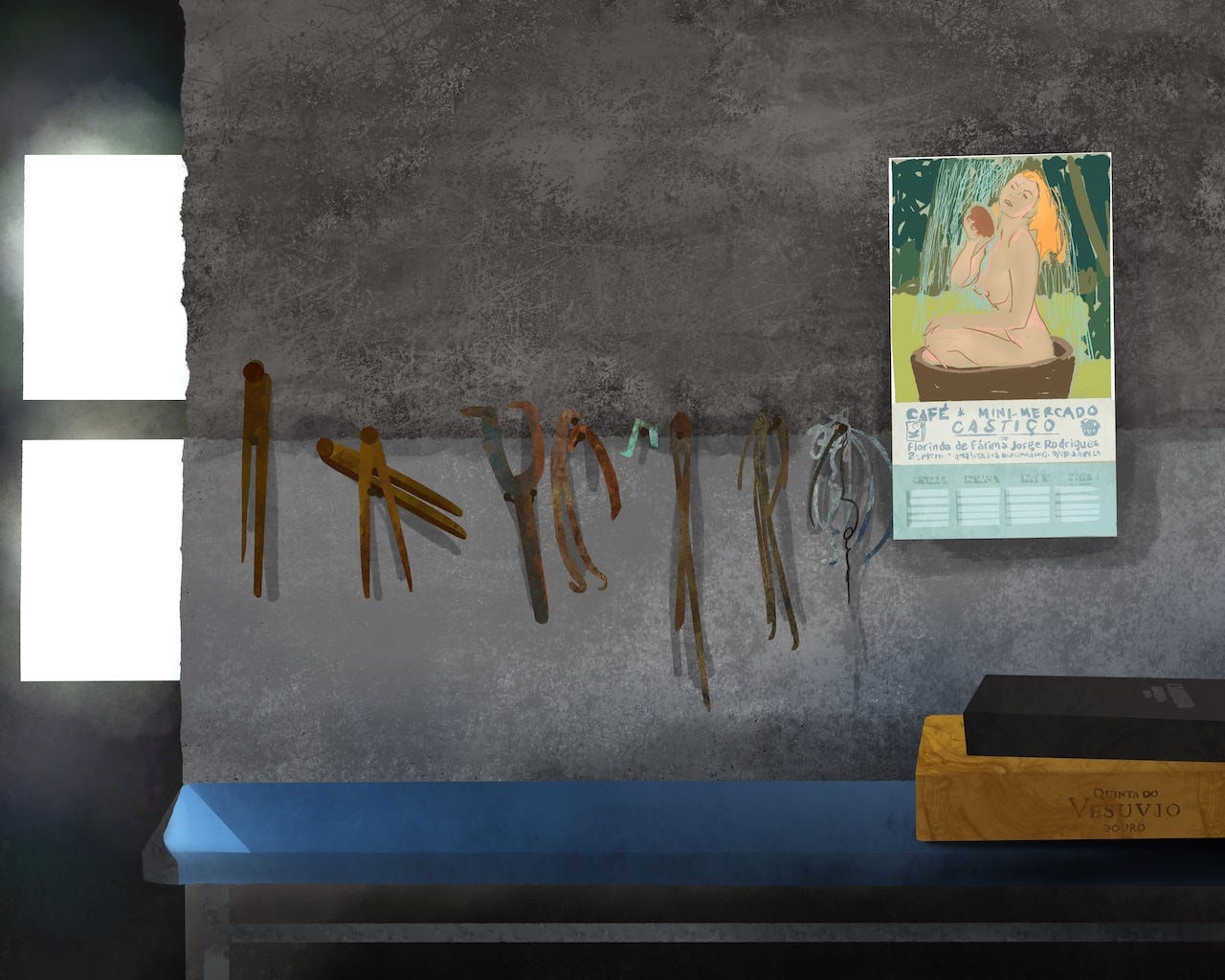

Wine is still made at many of the historic quintas, or wine farms, that dot the valley. Quinta da Senhora de Ribeira is one such property, a 44 HA estate in the Douro that George Warre purchased in 1890 as a source for Dow’s Port. Its winemaking cellar is still in active use at harvest, the grapes arriving in plastic bins before processing in modern lagares. This mix of old and new is everywhere in the Douro.

Quinta dos Canais has supplied Cockburn’s since the 19th century and is now, at 270 HA, one of the largest estates of the Symington group. The estate overlooks a breathtaking swath of river, and across the water sits Quinta da Vargellas, owned by Taylor Fladgate and occupied at harvest by its family elders, Alistair and Gillyane Robertson. (Read my essay, “Barefoot in the Douro,” about my visit to Vargellas.) In this image, Ports from strong vintages rest on a desk crowned with portraits of its progenitors; history captured in bottle and frame.

Rupert Symington is head of Symington Family Estates, whose brands include Graham’s, Dow’s, Warre’s, Cockburn’s, Quinta do Vesuvio, and more. As host he was warm and affable, but it was evident that he carried the weight of his responsibility to secure not only his own family’s legacy but also the persistence of Port writ large. The margins on this luxury good are surprisingly thin, and economics were foremost in his mind. “The secret to the Douro today is reducing cost,” he told me — just not at the expense of quality.

Port families employ household workers to cook, clean, and entertain guests, including the many visitors, like me, who arrive during the busy harvest season. Dinners may be lavish or homely; in this case there was squash soup, grilled chicken and sausages, fried potatoes, and a simple salad. The two women shown here have worked for the Symingtons for two and three decades, and while I wanted to speak with them, I learned they live a half an hour away by train or bus and the meal ended at 10:30 PM. I did not want to impose further upon their already long day.

Douro wines were historically field blends, with vines of Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Tinta Roriz, and others (even some white grapes), grown, harvested, and vinified all together. The results were often uneven, with some grapes overripe and others too tart. More recently, vineyards have been replanted to varietal monoculture, which allows viticulturalists to monitor development of each variety, choose appropriate interventions when needed, and zero-in on a proper picking time. The gains in quality offset a loss of rustic (nostalgic) charm.

Manual work is traditional in the Douro, where steep, rocky terraces, some as narrow as a single vine row, make mechanization not just impractical but impossible. Although this vineyard is gently sloping and widely spaced, harvesting here is nevertheless being done by hand. Top quality vineyards, and especially old vines and those that furnish single-quinta and vintage Ports, are almost always hand-worked. As I watched, the voice of these workers’ harvest song carried on the morning breeze, thin and reedy.

Granite troughs, called lagares, were ubiquitous throughout the Douro, and while they’ve now been supplanted by stainless steel and mechanized treaders, many houses still use them with their best fruit. Grapes arrive and are sorted before being added to the troughs, whereupon barefoot treaders stomp the clusters for four to eight hours; here a worker pauses for a sip from a tin cup of boxed wine. The human foot is considered ideal for this work, as it gently pops open the skins and warms the must to start the yeasts working. “Our most sophisticated method is foot-treading in granite lagares,” said David Guimaraens. “It applies intense but gentle physical action that produces the best extract. The beauty is that it’s a method that’s very well proven.” Still, most of the work is done in the vineyard, he said. “Foot treading isn’t about the skill of the winemaker. My skill is deciding when to pick, what to pick, and the blend.”

“The holy grail of winemaking was automatic lagares,” Rupert Symington told me, as we watched a tractor with a boom arm crawling along a vine row. “The holy grail of viticulture are the new automated pickers.” Symington had collaborated with a Spanish university and a German equipment company to develop a machine-harvesting approach suited to steep and narrow sites. We watched as the unit shook berries off their stalks and spewed them into bins. The tractor’s air intakes were getting clotted with leaves, and many clusters were getting left behind or dropping to the ground, leaving two dozen extra field workers to bat cleanup. The system only works on vines of a specific height, trained single cordon and spur pruned. It can only flow one way without breaking vine trunks; at the end of each row, the tractor had to back up to start the next. (A vineyard with cordons running in alternating directions would ease that problem, but training-over a vineyard is a multi-year exercise.) When I visited in 2019 there was only one Beta unit in existence, and it did not look like a home run to me. But it’s a start.

Grapes are handled multiple times prior to fermentation. Pickers often make multiple passes in a vineyard, selecting that day’s ripe clusters and leaving others for a second or third round. At the grape reception area, workers review each bin, winnowing out matter other than grapes (MOG) and any clusters with mold or damage before sending them on for vinification.

James Symington worked principally in sales and export, but as a lifelong member of the wine trade he likely knew his way around a cellar, and he seemed to delight in chatting with this young winemaker. She is one of the few female enologists I’ve observed in the Douro; while I’ve seen many women working as pickers, domestic staff, and treaders, the preponderance of technical cellar workers has been male.

Modern stainless lagares use mechanical agitation to crush the fruit, but some producers use a mix of foot treading and mechanical action. Regardless, it’s critical to extract maximum color and flavor at this step because the clear grape spirit added during fortification — which ends up being 20 percent of the Port — dilutes the color. Port is one of the few red wines that do not go through malolactic fermentation; it doesn’t have a chance to do so before fortification, but the abundant residual sugar tames its tart malic acid.

After vinification, the red must is pressed to extract maximum flavor, color, and tannin. Some quintas still use large basket presses like these, which, according to David Guimaraens, do the job without what he calls “over tumbling.”

Port ages in large, airy lodges in the city of Vila Nova de Gaia, across the Douro from Porto. The cooler, more humid conditions here are better suited for Port aging than the hot, dry climate of the upper Douro, and the Port trade has contributed to the success and wealth of these seaport cities.

Many Port lodges maintain an in-house wood shop to care for their barrel stocks. Tawny port ages in large tapered barrels called pipes which hold 550 liters of wine. Coopers carefully husband these old barrels, taking them apart when needed, shaving and planing them, re-fitting them into tight new vessels, and cycling them back into use. The houses are jealous of their stocks: “We’re desperate for barrels,” said Robert Bower, of Taylor’s, “because we can see Tawny growing as a category.”

Port gets made; Port gets sold. At the lodges in Vila Nova de Gaia, many houses offer tastings, tours, exhibits, restaurants, and lodging for tourists. They also employ marketing, sales, and export teams who juggle the preponderance of the wine, which is sold outside of Portugal. Rui Ribeiro is market manager for U.S.A. for Symington’s, but his vast knowledge makes him a strong ambassador both for the company and the category. Here he led a tasting of Dow’s and Cockburn’s tawny Ports, including 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-year bottlings, plus colheitas (single harvest) from 2002 and 1994. The wines were scintillant.

Port seems aristocratic, even imperialistic, a luxury good for few. But Port shippers aren’t the only families whose legacy, whose history, factor in the equation. There are multitudes of people, working at all levels of the enterprise, whose livelihoods are entwined with Port’s success. If Port falls from fashion, if climate change destroys the Douro’s viability as a wine region, if an aging population and labor shortages mean grapes go unpicked, if the small farmers who sell grapes to the Port houses lose their generations to the cities, if the cost of production soars so high as to make Port untenable, what then? Did centuries of family struggles count for nothing? Port has been a story of survival, of persistence. Change is the only constant.

My visits to the Douro were paid for by producers and their importers, and all travel, hospitality, and wine samples were provided. I’m grateful to the families of the Taylor-Fladgate and Symington estates and their many colleagues and coworkers for the warm reception and opportunity to glimpse their work.

My tools are iPad Pro 12.9″ fifth generation, Apple Pencil second generation, and the app Procreate v. 5. Like all material on this website, these images are copyright Meg Maker and their use in any medium without permission and attribution is not allowed. Please contact me about licensing, usage, permissions, or to discuss a new commission. Thank you!